Limassol is a city in flux. Once a coastal hub of grassroots creativity, tight-knit neighborhoods, and modest local enterprise, it now finds itself on the fast track to something entirely different. The city has turned into a polished destination tailored for international capital, high-end tourism, and foreign enterprise.

The change has not gone unnoticed among those who’ve called the city home for decades. While the skyline is increasingly dominated by glass towers and luxury developments, the real cost of this transformation can be seen at street level. Locals experience rising rents, disappearing communities, and a creeping sense of displacement. Limassol is no longer just growing; it’s changing character, and not everyone has been invited for the ride.

Gentrification is an urban makeover that attracts wealthier residents, reshapes infrastructure, and leaves original communities struggling to keep up. In Limassol, many find the speed of this shift is unsettling. Property prices have exploded, the cost of living has surged, and working- and middle-class families are pushed to the margins. Artists, in particular, are among the first to feel the squeeze.

Danae, an artist who goes by the handle @santa_nomeni, has documented these transformations from up close. Speaking to Politis, she describes a city losing touch with its roots.

“I think the biggest issue is that Limassol is no longer viable for the people who made it,” she said. “Most of my friends have left. They’ve moved to other countries where they can actually afford to live. Others have become nomads, floating between continents just to make ends meet. Cyprus used to be home. Now it’s just a stopover.”

Danae’s work was recently featured at the Street Life Festival, where she painted a mural based on a close friend’s life, someone constantly torn between staying and leaving, unable to build a stable life in the city she loves.

Danae's mural at the 2025 Street Life Festival in Limassol

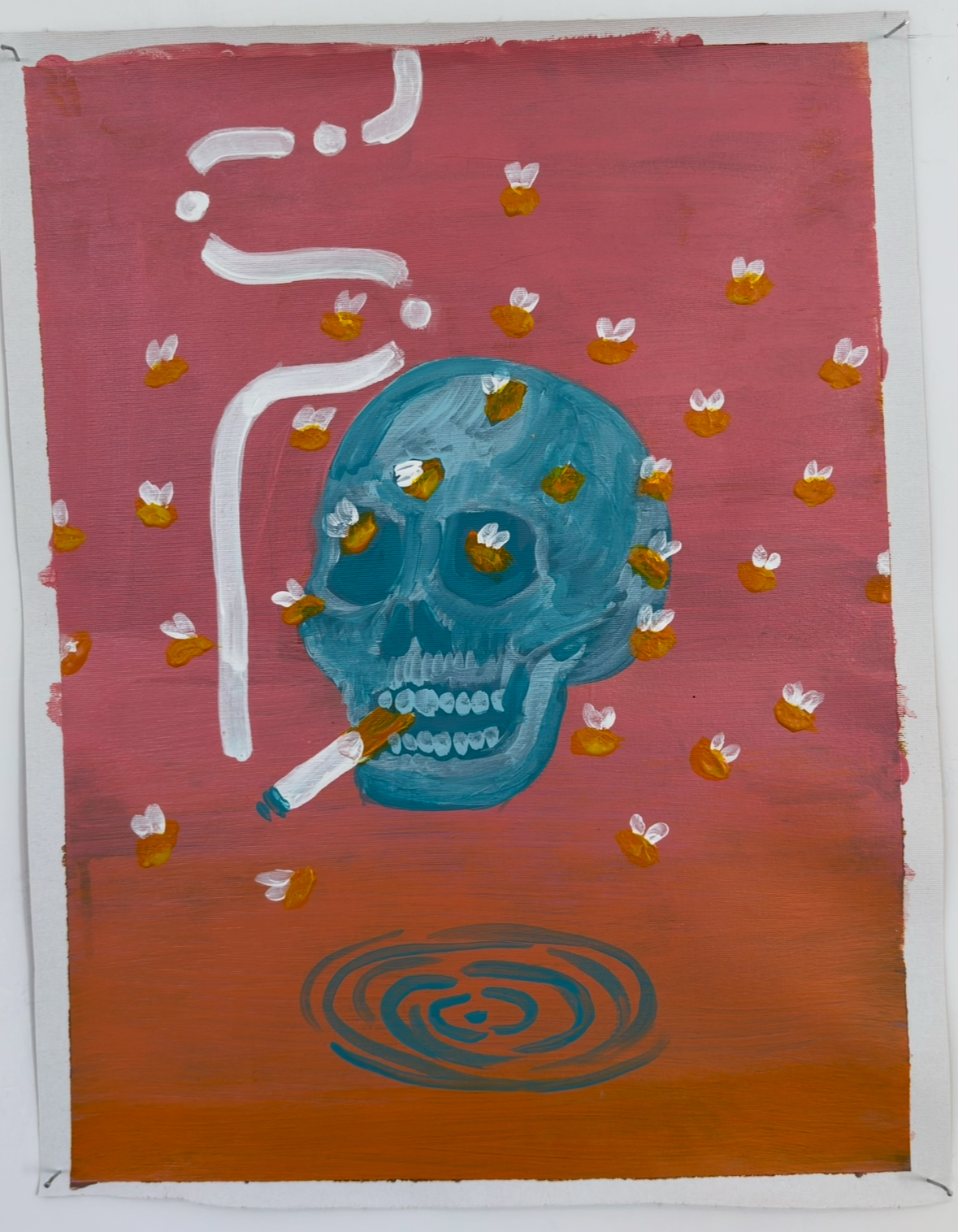

In July, Danae hosted her first art exhibition framed around Limassol’s gentrification symbols. Her canvases depict contradictory scenes of everyday life in the city.

“It’s about that emotional state of suspension,” said Danae. “People who are genuinely trying to live here, to stay rooted, but find it impossible. Everything is just too expensive, too unstable, too indifferent.”

But this isn’t just a financial story. There’s a deeper social wound at play. “People say Cypriots stay with their parents until 40 because of strong family bonds,” she said. “But no one dreams of being dependent. That’s not tradition, that’s economic necessity. It’s a sign that the system isn’t working.”

Even cities like Manchester or London, long known for their high cost of living, seem more livable to Danae’s peers than Limassol does today. “That says everything, doesn’t it? Places with higher minimum wages, better services, public arts funding and so on. Even they are more affordable than where we’re from.”

Still, Danae remains in Limassol - not out of comfort, but defiance. “An artist’s role isn’t just to decorate a space or produce something marketable,” she says. “It’s to observe, question, archive, and resist.” In a city rapidly reshaped by luxury towers and investment visas, her work becomes a kind of documentation, a quiet protest against erasure. “We’re the memory-keepers. The ones who try to make sense of what’s happening when the rest of the city is too busy building over itself.”

But surviving as an artist here is another story. Without adequate public funding, affordable studios, or consistent community support, many are forced into fragmented freelance work or leave altogether. Those who stay, like Danae, patch together residencies, side jobs, and commissions - rarely enough for stability, often at the expense of their creative momentum. “We’re expected to romanticize the struggle, but it’s exhausting,” she says. “Still, I feel a responsibility to stay. Because if all the artists leave, who’s left to tell the story of what we’re losing?”

'Would you rather burn in guilt or drown in poverty?' - Acrylic on Canvas

Part of the blame, she believes, lies in policies that prioritized foreign investment over local resilience. The infamous “golden passport” programme, which granted EU citizenship to wealthy foreign nationals in exchange for property investment, created a construction boom, with luxury towers rising quickly across the city. Many now sit vacant.

“It’s surreal,” Danae says, “the towers stand there, glowing and empty, like monuments to someone else’s city.” Many of these newly built skyscrapers - pitched as emblems of progress and international prestige - remain largely unoccupied, bought up by offshore investors or left half-finished. To Danae, they’re less symbols of growth and more ghostly placeholders, towering reminders of who was forced out to make room for them.

Over the past decade, rising rents and speculative real estate projects have priced out hundreds of young families, many of whom relocated to Limassol’s outer villages and rural fringe. In the recent Limassol fires, several of those same rural areas were among the hardest hit - homes burned to the ground, lives uprooted once again.

For Danae, the contrast of illuminated, lifeless skyscrapers and darkened, burning villages captures the cruel irony of Limassol’s urban transformation. It’s a visual metaphor too painful to ignore, and one Danae has begun to sketch obsessively. “I don’t know how else to process it,” she admits. “Maybe that’s the value of being an artist. Not just to survive, but to not look away - and to make sure no one else can, either.”

“These buildings were never meant for us,” Danae said. “They were built to funnel wealth. And now, they’re monuments to a model of development that left locals behind.”

At the same time, Limassol is branded as a business paradise for international companies, particularly in tech and finance. “We’ve become a FinTech island,” she added. “Like a miniature London just without the safety nets or the public investment.”

What’s most striking, however, is not just the scale of Limassol’s vertical growth, but the absence of foresight behind it. As foreign capital poured into the city’s luxury office and residential real estate, government planning failed to tether this investment to the public good. Unlike other cities where developers are required to contribute to community infrastructure - from green spaces to parking, schools, or accessible transit - Limassol’s building boom arrived with no binding obligations to improve the surrounding urban fabric. The result? Towering office blocks surrounded by traffic-choked roads, eroded public space, and local residents increasingly shut out of both the conversation and the neighborhood, as Danae describes.

Government officials frequently point to the macroeconomic gains of this transition. But Danae, like many others, asks a simple question: Who benefits?

“If your policies are bringing in money, where is it going? Who’s actually seeing that profit? It’s certainly not artists. It’s not low-income families. It’s not people trying to make a life here from scratch. It’s the same elite, untouched by crisis, who are now simply richer.”

'Onesilus' - Acrylic on Canvas

For all the talk of progress, the promises of trickle-down economics ring increasingly hollow in Limassol. The theory that wealth generated at the top will eventually benefit those at the bottom has found little footing on the city's uneven streets. While developers, real estate firms, and a handful of high-end service sectors have seen profits rise, the vast majority of residents report no measurable improvement in their daily lives. Rents have surged, wages remain stagnant, and public infrastructure -from transportation to firefighting readiness- struggles to keep pace.

Even some of those who’ve profited from the transformation admit unease. “It’s hard to celebrate a booming market when it feels so disconnected from the people who live here,” says a property consultant who preferred not to be named. “I’ve sold apartments no one will ever live in”. Their discomfort highlights a growing contradiction: those who benefit financially are increasingly questioning whether the system they rely on is sustainable - or fair.

For artists, the impact has been devastating. Public funding is minimal. Affordable studios are vanishing. Venues for performance and exhibition are increasingly controlled by commercial or foreign entities.

Danae notes how even cultural institutions are now catering to outside audiences. “In Pattihio theatre, for example, the signage is in Russian. The programme is increasingly closed off to local productions. Russian companies are often the only ones featured in large-scale projects.”

Meanwhile, creatives are being pushed into shared spaces or forced to work from home, where the noise of everyday life interrupts the quiet needed to produce meaningful work. “Exhibiting your work has become a luxury,” she said. “It takes money, time, contacts. Without those, you’re invisible.”

This invisibility is what gentrification often leaves in its wake. “Everything is becoming cleaner, shinier, better-packaged,” Danae said. “For tourists, for investors. But if you don’t fit into that picture - if you’re not part of this polished success story - you’re pushed to the margins. It’s deeply unfair.”

Yet despite the challenges, she hasn’t given up. Danae still believes in the possibility of a more inclusive future for Limassol.

“There’s always hope. But change requires political will and pressure from society,” she said. “We can’t keep sacrificing cultural identity and social justice for the sake of development. That’s not growth. That’s erasure.”

What she envisions is simple: affordable homes, workspaces for artists, and a cultural environment that nurtures creativity rather than commodifies it. But above all, she calls for a shift in how society values its artists not just financially, but emotionally.

“People need to feel seen. Heard. They need to know they belong here and that this city is theirs too,” she said. “Not a place they have to leave in order to live.”

@Santa_Nomeni