In February 2024, staff at Booyoung Co.’s Seoul headquarters gathered for the company’s traditional New Year’s address. What began as a routine speech turned into a corporate milestone. Founder Lee Joong-keun, the 84-year-old billionaire behind one of South Korea’s largest construction firms, announced that every employee would receive 100 million won ($72,000) for each baby born, retroactively covering the past three years.

The room fell silent before erupting into applause. “I was speechless,” recalls Hong Ki, a 37-year-old communications manager and father of a three-year-old at the time. “It was so absurd that I couldn’t even sleep, wondering if it was for real.” It was, and soon after, Hong and his wife, who also works at Booyoung, decided to have another child.

A rooftop play area at Krafton’s daycare center in Seoul. Photographer: Tim Franco for Bloomberg Businessweek

A country facing demographic crisis

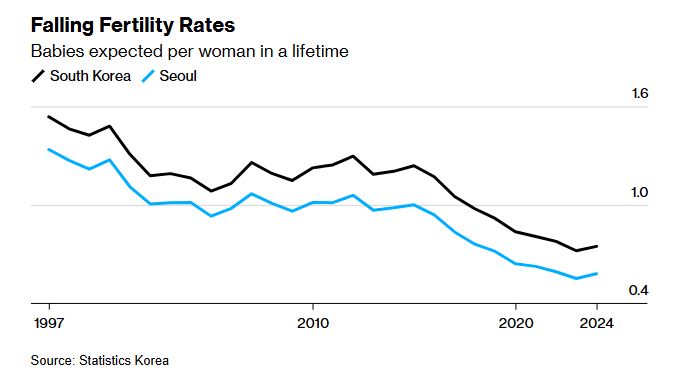

South Korea’s fertility rate stands at just 0.75 births per woman, the lowest globally. If the trend persists, the population could shrink by nearly a third by 2072. The implications are stark: a shrinking workforce, dwindling tax revenues, empty schools, a rapidly ageing society, and a military struggling to fill its ranks.

The government has poured hundreds of billions of dollars into incentives, cash allowances, housing subsidies, tax breaks, yet success has been limited. Companies, fearing a future with too few workers, are now stepping in.

Corporate baby bonuses

Booyoung was the first mover and remains the most generous. The company says its scheme encouraged 28 employees to have children last year, five more than usual, and has transformed its culture. In a country where long hours and rigid office hierarchies have discouraged parenthood, staff now joke: “Get married, get the money and buy a house.”

Other big businesses have followed. Krafton Inc., the video game developer behind PUBG, offers $43,000 at birth and an additional $29,000 in instalments until the child turns eight. Korea Aerospace Industries pays about $7,000 per child for the first two births and $22,000 for a third. Conglomerate Hanwha Group has distributed more than $820,000 across its affiliates, with surveys showing 86% of recipients felt encouraged to have more children.

Doosan Enerbility, Posco, SBW and Kumho Petrochemical have also introduced cash-for-babies schemes. While the sums vary, the rationale is the same: investing in workers’ families is cheaper than confronting a future without a workforce.

A global concern

Falling birth rates are not unique to Korea. Japan, China, much of Europe and the US face similar challenges. US President Donald Trump has floated the idea of a $5,000 baby bonus, while China recently pledged 3,600 yuan ($500) annually per child under three.

South Korea’s government has long experimented with incentives: subsidised childcare, extended parental leave, cheap mortgages, even funding vasectomy reversals. In some areas, families can rent public flats for as little as $22 a month, while in Seoul parents receive over $5,000 in housing aid per baby. The government’s target is to lift the fertility rate to 1 by 2030, though the replacement level is 2.1.

Signs of progress - and scepticism

There are early signs of a rebound. For the first time in nearly a decade, the national birth rate rose last year, with a 7% increase in the first five months of 2025 compared with the same period in 2024. Marriages are also up. “We see it as a structural bounce back, not a temporary one,” says Joo Hyung-hwan, head of the Presidential Committee on Aging Society and Population Policy.

But experts warn against complacency. Some argue the uptick may simply reflect postponed weddings during the pandemic. “While the allowance is an important token, flexible work arrangements are likely more crucial,” says Ko Woo-rim, professor of population policy at Seoul National University. Others stress the need to ease pressure in Seoul, where the cost of raising children is highest, by making smaller cities more attractive to families.

Retention and recruitment benefits

Beyond demographics, companies say family-friendly policies boost loyalty and help attract talent. Krafton offers emergency babysitting, guaranteed cover during parental leave and career protections for staff taking time off. Its daycare centre, open until 9:30 p.m., is now more frequented by fathers than mothers, a cultural shift in a nation where men have traditionally been absent from childcare.

At Booyoung, none of the roughly 100 employees who received baby bonuses have left the firm. “You’d want to work hard and keep the company successful so that we all continue to enjoy the benefits,” says Hong, whose family grew thanks to the policy.

For employers and policymakers alike, the message is clear: investing in children may be the most important investment of all.

Based on reporting by Bloomberg