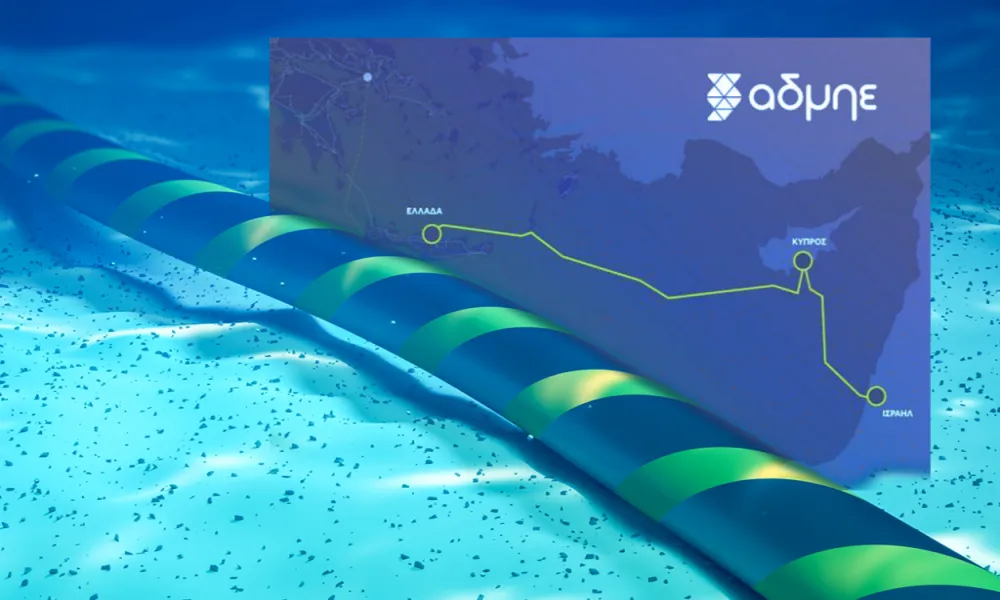

Well, it’s not a new rodeo. The prospect of connecting Cyprus to Greece through an underwater cable, has been in the public domain for years. The project, more widely known as the EuroAsia Interconnector, promises to pull water out of the mire of energy isolation and integrate the island state into the European network, offering alternative supply in times of crisis.|

Its supporters point to the fact that such a connection will forge an energy security shield, ending Nicosia’s total dependence on fossil fuels and the possibility of supplying or importing energy to and from a wider, pan-European network. As the same argument goes, the possibility of utilising more renewable energy sources will be substantially strengthened, as additional production will not be lost (the way it is now), but transferred on to the network.

Not to mention the established geopolitical value of such a reality. Cyprus turning into an energy hub in the Eastern Mediterranean, deepening relations with Israel and Greece in the process, not of course excluding tightening networks with the EU.

Dissenting voices warn of the massive costs and technical challenges. The cable will be the deepest and longest (1200 km) globally, with completion timeframes miles longer.

THE PROS

Energy Security

Greatly reducing our country’s dependence on fossil fuels and providing alternative supply in times of crisis. Currently, Cyprus is dependent on the EAC, producing admittedly expensive energy (35 cents per kilowatt), using fuel oil. Photovoltaic parks that have developed over the past few years, appear problematic realities. Beyond the exorbitant charge (28-30 cents a kilowatt, while the cost is under 10), their use is limited, as there is no system in place to store the surplus energy. During another record tourist summer this year, the power cuts during high demand evenings could not be described as anything less than an oxymoron, with the surplus energy from photovoltaics essentially dumped, as there is no way to store and integrate this power into the grid.

EU Connection

Our energy isolation ends, with the island harmonising at long last with the declared goal of a common energy market. In joining this market, Cyprus will take yet another step forward in deepening its relations as a member of the EU hard core.

Renewable sources

The GSI will facilitate a significantly greater amount of surplus green energy being supplied or imported through the interconnected network. Furthermore, Cyprus will finally harmonise with green European directives on pollutants. Cyprus has now paid more than 300 million euro in pollution fines mainly due to the Vassiliko and Dheryneia power stations.

Geopolitical value

It further strengthens the Greece-Cyprus-Israel synergy, with Nicosia turning into an East Med energy hub, while also offering up prospects of supplying Turkish-Cypriots too, in the eventuality of a Cyprus settlement and even a possibility of connecting with mainland Turkey, 40-50 km to the north. The prospects take on much greater dimension if Gulf countries join the newly forged grid, either through the use of natural gas or extensive photovoltaic parks that can enrich the network with massive amounts of electricity.

THE CONS

Heavy cost

As things stand today, this is estimated around 2 billion, with finance minister Keravnos, not hesitating to stand against the project publicly on many occasions, referring to its ‘non-viability’. As the same argument goes, investors will never be able to make profit, nor perhaps break even.

Technical difficulties

So much so that they cannot be possibly overcome, as proponents of non-viability argue. We’re talking about the deepest and longest undersea cable in the world, at a length of 1200 km, with technical challenges including the Eastern Mediterranean seaboard depth, even reaching 3 thousand feet in certain areas.

Geopolitical risks

Turkey is already crying foul or scaremongering, either diplomatically, through a rhetoric of threats or tangible on the ground threats across the EEZ involved in the project. It recently moved warships near the Greek island of Karpathos, preventing an Italian research vessel from measuring the depth of the seaboard along the route of the cable right through to Cyprus shores. Some believe that Ankara’s play is raising the implementation stakes. Not to mention obviously that no EEZ has been delineated with Turkey in the Eastern Mediterranean, with the Turks claiming massive offshore plots and blackmailing both Greece and Cyprus to enter a dialogue in acceptance of such demands, without respecting international law.

Time-consuming

Even if everything runs smoothly, we’re looking at a decade of construction, so nothing to show for in terms of providing fast-track solutions to the current energy crisis. And even more pertinent to the changing energy realities, the costly process of cable laying will become a technical dinosaur by the time it’s implemented. As we tussle and argue over the project, energy projects on a global scale, increasingly focus on hydrogen and nuclear, way beyond photovoltaics and wind energy.

Too little, too costly?

Weighing up these considerations, some claim that geopolitical arguments in favour of the project are erroneously based on technical realities of the previous decade. In the Western Mediterranean, such works were launched in the early 2000s and have already gone a long way towards strengthening the European energy market. But we’re only starting out now on the eastern sector, (if they do start out that is), with tinges of corruption hueing the project and implementation, should things be cleared up, ten years down the road.

The Western Mediterranean includes a number of projects, including the connection of Italy-Malta, Sardenia-Corsica and Spain with the Balearic Islands.

The SACOI & SACOI 3, one of the oldest undersea cables in Europe, connects the Italian peninsula with the islands of Sardinia and Corsica and is currently undergoing an upgrade. There’s also Romulo, the electricity connection between the Spanish peninsula and the Balearic Islands, which integrated the islands’ grid to the Iberian electricity market, creating competitive production in the Balearics.

The Malta-Italy connection has been active since 2015 through a 120 km cable. Italy and Montenegro are also connected (HVDC Interconnector). The 455 km undersea cable became operational in 2019 and joins Italy to the western Balkans. The GRIT interconnection joined Greece and Italy since 2002. It is 163 km long and brings together high voltage systems. 2023 also saw the completion of an exclusively Greek project, joining the mainland with Crete (Ariadne Interconnector), through the largest undersea cable in the Mediterranean to date (500 kV DC).

Conclusions

Through a strategic and European lens, this project is of significant important and could forge a shield against any challenges to the energy future of Cyprus. Realistically speaking however, its implementation is technically tough, time-consuming and costly. Europe has heavily invested with 657 million euro, with both Greece and Cyprus stepping in as guarantors to ensure implementation. Having said that, Israel’s active participation would have greatly sharpened the GSI’s credibility credentials. But Tel Aviv has been in a state of war for almost two years.

In general terms, an independent electricity pipeline running through to Cyprus will always be useful as an energy link to this troubled region and suddenly raising the island from the depths of energy isolation to a surface of an Eastern Mediterranean hub.

At practical and crucial daily level, the pipeline can bring electricity home any way it is produced (natural gas, wind, photovoltaics, hydrogen, nuclear), as such improving internal market competitiveness. The inability of the state to make natural gas at Vassiliko a reality, the EAC’s incapability of a technological upgrade and the greed of the local photovoltaics producers market, have condemned the Cypriot consumer to a vastly unfair situation. The most expensive electricity in Europe.