“The money’s not here. Your money’s in Joe’s house… and the Kennedy house… and a hundred others.”

It’s a line from It’s a Wonderful Life (1946), one of my favorite films, and one that always feels current. A housing crisis, an elite class, branding the landscape to be forever commemorated, inequalities. Eighty years later, ordinary people’s problems not only did not disappear, but they also metastasized: money turned into homes through mortgages and loans, wealth hoarding...

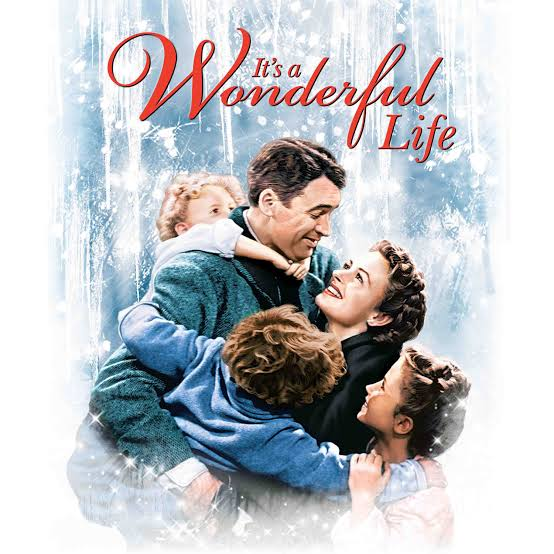

But beyond the timeless messaging and the kind of economics we all understand, Frank Capra’s It’s a Wonderful Life (1946) remains the pinnacle of holiday cinema, because it’s a masterclass in narrative economy. Each scene, from the opening shot to the intimate interactions between characters, demonstrates how minimal means can achieve maximal emotional impact.

Starring James Stewart as George Bailey, the film chronicles the life of a man who constantly balances personal ambition with responsibility to family and community. Donna Reed and Lionel Barrymore support Stewart in roles that highlight moral contrasts and human complexity, all within the intimate world of Bedford Falls.

A prime example of script economy is the opening sequence in Bedford Falls at Christmas: a snow-covered small town with bustling streets, festively decorated windows, and lampposts. The camera glides through the town, instantly conveying the community’s structure and warmth. A gentle orchestral score underscores the scene, evoking nostalgia while hinting at underlying tensions. Dialogue is minimal, just snippets of greetings and laughter, yet in just a few minutes, Capra communicates the time period, the town’s charm, the social dynamics, and the emotional tone, all without heavy exposition.

This opening works as a cinematic shorthand: audiences immediately understand the world George inhabits, the stakes of his social network, and the tension between individual desire and communal duty. Music, visuals, and minimal dialogue carry a triple load, setting, tone, and thematic framing, making it a historic example of economy of storytelling.

Released in 1946, the film reflects postwar American anxieties, economic pressures, social responsibility, and moral choices, while delivering a timeless meditation on human connection. Its craftsmanship lies in how every narrative beat, every visual choice, and every moment of humor or pathos serves the story’s emotional and ethical core.

It’s a Wonderful Life is a holiday tradition but also a movie worth watching. And there is a lovely message: a life’s true worth is measured not by wealth, but by the invisible ripples of kindness it creates.

So, watch this lesson Capra delivers with cinematic brilliance: Life is hard but it’s also wonderful…