How justified is Tufan Erhürman when he protests the recent Cyprus-Lebanon agreement delimiting the EEZ of the two countries, claiming "that the Greek Cypriot leadership cannot continue to sign agreements on behalf of the entire island without the will of the Turkish Cypriots"?

No one doubts that when Nikos Christodoulides signed the agreement delimiting Cyprus' exclusive economic zone with Lebanon, he had in mind the fundamental goal of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, that every such agreement is a small victory and strengthens the state entity of the Republic of Cyprus, which since 1974 has been challenged by Turkey by all means and methods. In this context, even Cyprus' accession to the EU was approached similarly, although what had been agreed upon was something else. The idea was that Cyprus' EU membership would act as a catalyst for a solution through the return of the Turkish Cypriots to the Cypriot state. In the same spirit, this policy, even in its extreme emphasis, especially in the energy sector, seeks to exclude Turkey and by extension the Turkish Cypriots from any cooperation, whether it concerns drilling, gas pipelines such as East Med, or even laying electricity transmission cables. The Turkish Cypriots are also rightly suspicious that every time the Cypriot President invites Ankara to direct talks, he knows very well that this action politically sidelines the Turkish Cypriot community.

Desires and Realism

On the other hand, Mr. Erhürman believes that the Turkey-dependent administration he leads is capable, without a Cyprus solution, of participating in the signing of such agreements. No one disagrees with him in principle, that Cyprus has two equal partners with equal sovereign rights, since they jointly founded the state in 1960, and that the will of the Turkish Cypriots should not be excluded. But how could they, in this particular case, without a solution and without participation in the government, have a say in the recent signing of the agreement with Lebanon and earlier in similar agreements with Israel and Egypt?

What Erhürman should realistically consider at this moment is whether the agreements signed by the Republic of Cyprus are also in their own interest.

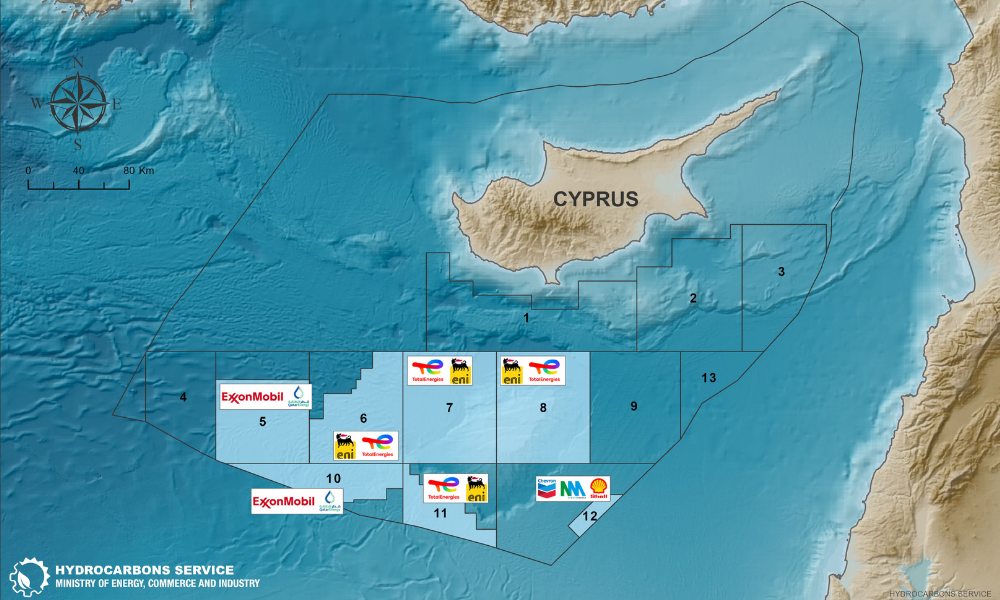

In short, do the 50:50 agreements on EEZ sharing between Cyprus and Egypt, Israel, and Lebanon harm the interests of the Turkish Cypriots? The answer is certainly no, as these agreements serve the interests of the Republic of Cyprus and all its residents, that is, both Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots. The Cypriot natural gas, estimated at over 25 trillion cubic feet, the pipelines, cables, and terminals that may be constructed, will benefit all residents of Cyprus, either through access to cheaper electricity, the inflow of millions of euros annually into the common treasury from hydrocarbon exploitation, or by turning the country into an energy-based innovation hub.

Turkey

By contrast, at present, Turkey, in the way it operates, works against the well-understood interests of the Turkish Cypriots. How?

-

It has forced the Turkish Cypriots to sign an EEZ sharing agreement in the north with a 70:30 split in its favor, while the Republic of Cyprus signs 50:50 agreements with all its neighbors.

-

It has repeatedly called on Egypt to terminate its EEZ agreement with Cyprus, claiming that islands have no EEZ and that the maritime area in the Eastern Mediterranean should be defined by Ankara and Cairo, excluding Cyprus.

-

It has urged Israel not to accept the delimitation agreement with Cyprus, even claiming that Block "Aphrodite" does not belong to Cyprus, that is, to Greek and Turkish Cypriots, but to Israel.

-

It has reacted negatively to the Cyprus-Lebanon agreement, claiming Lebanon is granting Cyprus much more maritime area than it is entitled to. For the past 18 years, using Hezbollah’s influence in the Lebanese parliament, it has prevented ratification of the delimitation agreement signed with Cyprus.

-

Since 2011, when the first major Cypriot gas field was discovered, it has tried, and largely succeeded, to prevent any exploitation of Cyprus' natural gas, either by contesting the boundaries of Cypriot blocks or by using its naval forces to expel drilling platforms and specialized cable-laying vessels.

The hard core

Turkey does not do these things to protect the interests of the Turkish Cypriots in the region. For Turkey, the Turkish Cypriots are a tool for pursuing a grandiose policy in the Eastern Mediterranean. The issue for Turkey is not just the technical limits of EEZ delimitations but the hard core of Turkish policy in Cyprus and the Eastern Mediterranean. Let us examine its regional policy more closely.

-

Ankara's basic position has remained unchanged for decades. It does not recognize the Republic of Cyprus and claims that the Turkish Cypriots, as "equal founders of 1960," have full sovereign rights over the maritime zones. From this perspective, any delimitation agreement signed by Nicosia is deemed "illegal" and "unilateral." Ankara insists that Turkish Cypriots must participate in every agreement or that a Cyprus solution must precede it. Yet, by claiming the lion's share for itself, Ankara demonstrates that the Turkish Cypriots are merely a pretext and means to achieve its demands, as its policy harms not only Greek Cypriots but also Turkish Cypriots.

-

Ankara does not recognise that islands have full EEZ. Contrary to the Law of the Sea, which grants full rights to island states, Turkey, having not signed UNCLOS, claims that islands have "reduced" or even "zero" effect when they lie in the continental shelf of a large landmass. Thus, it considers that Cyprus cannot delimit maritime borders with Egypt, Israel, and Lebanon as it has, because much of these zones fall within Turkey’s continental shelf according to its view.

-

The "Blue Homeland" strategy. Ankara's strong opposition is also part of the "Blue Homeland" doctrine, aiming for broad control in the Eastern Mediterranean, from Libya and the Aegean to Cyprus. The agreements of the Republic of Cyprus with Egypt (2003), Israel (2010), and Lebanon (2025) create a southern arc of maritime zones limiting Turkey’s strategy. Therefore, Turkey seeks to block politically and operationally any action consolidating Cyprus' maritime claims.

-

Conflict over regional energy architecture. Cyprus' agreements act as a gateway for cooperation with Egypt and Israel, both in hydrocarbons and electricity interconnection. This network of cooperation, albeit incorrectly, excludes Turkey from the Eastern Mediterranean energy architecture. The only country that could lift this exclusion is Cyprus as a hub for the entire region. However, without a Cyprus solution, Nicosia is inevitably aligned with Israel.

Things would be much easier for Turkey if it stopped the absurdity of seeing a small island like Cyprus as a threat. Matters would be infinitely simpler if, through a solution and reunification of the island, the Turkish Cypriots regained the role of balancing Nicosia’s stance toward Ankara. Perhaps then Greek Cypriots, without the insecurity and fear generated by Turkey’s daily bullying, could recognize that an economic relationship with this neighboring country is highly beneficial for all. A Cyprus solution could allow the economy and its people to take action, removing the iron curtain created by the 1974 coup and military invasion, which ultimately did not solve problems but created more.