It’s a Wednesday afternoon on Patroklou Street, in the heart of the walled city, in the neighbourhood of Chrysaliniotissa — an area that feels frozen in time. Some restored mansions stand beside shuttered workshops. Occasionally, a few foreign visitors wander through the narrow streets. Only the smell of oil betrays a sign of life behind a faded green door.

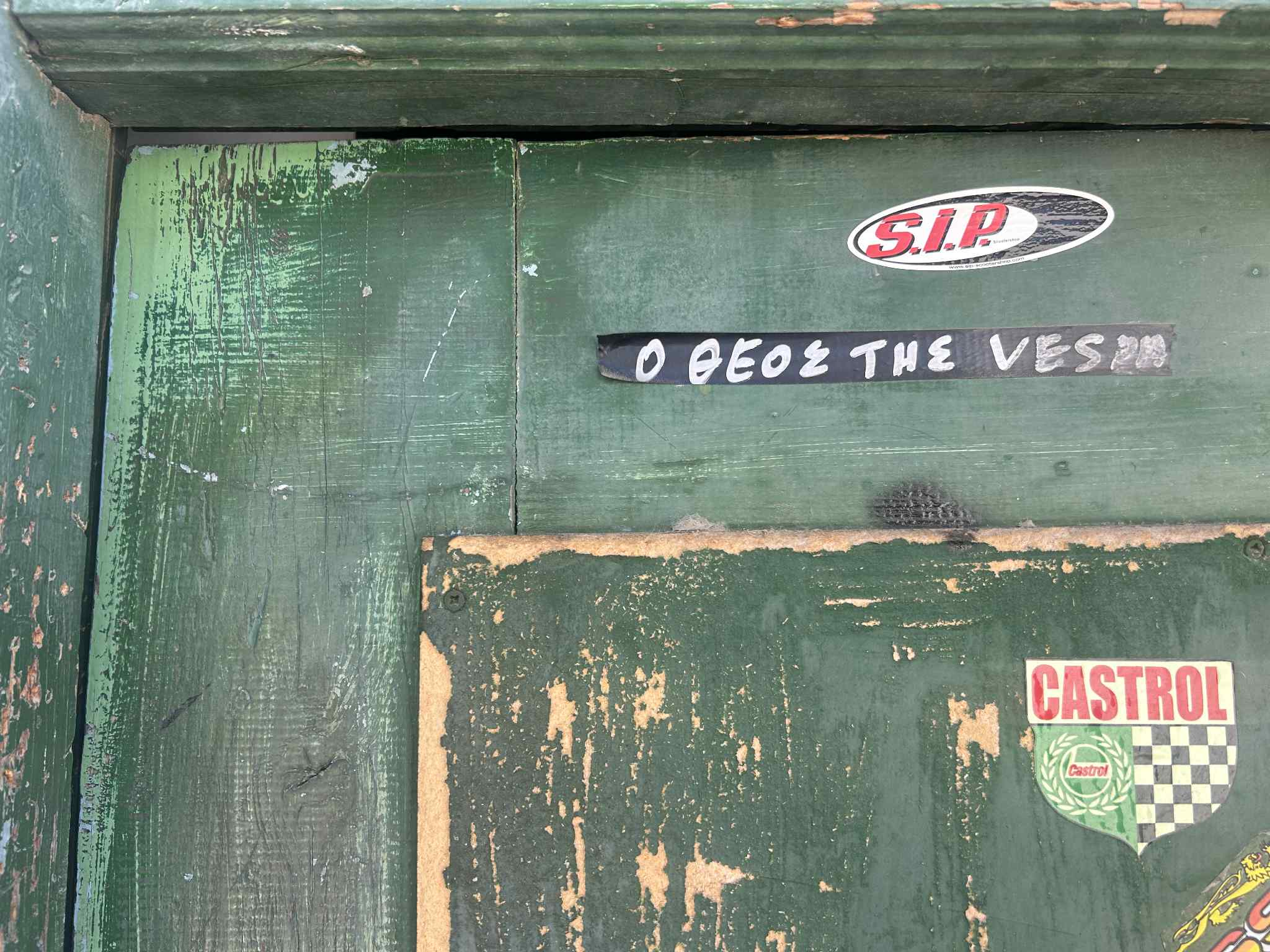

On the door, a strip of tape reads “The God of the Vespa.” Outside, two vintage metal signs evoke scenes from cult films of the 1960s, when Vespas were iconic — a classic symbol of a cinematic era. From inside comes the unmistakable (and, for some, irritating) sound of a two-stroke engine. These are the “sirens” that lead you to Chrysostomos’s garage…

Inside, rows of Vespas greet you — some half-dismantled, others nearly ready to hit the road again. The workbench is covered with scratched tools, greasy rags, and the distinctive smell of petrol. Chrysostomos — known to most as “Tommy” — welcomes us with a smile, his hands black with grease.

“I started in 1995. I was 15. My father, Fotis, had been working here since 1960. To give you an idea, the first Vespa arrived in Cyprus in 1952. This place used to be both our home and the workshop.”

From working-class ride to collector’s icon

In Fotis’s day — hence the name of the garage, “Restored by Photis” — the Vespa was a vehicle for ordinary people, for workers. “Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots used to come here. He repaired bikes for everyday people. Not like today, where the Vespa is more of a vintage collector’s item. It started as a working-class ride and ended up a sought-after gem.”

Many younger owners visit the garage today because they remember riding on Vespas with their grandfathers or fathers. Others bring in old family scooters for restoration. Some even send over frames and parts from abroad for Chrysostomos to work on.

“It’s like an inheritance. The Vespa community is quite large. The last classic models were made in 1990, when the PX line was discontinued. Since then, they’re passed from hand to hand. In Cyprus, we’re lucky — in some countries, old vehicles had to be scrapped by law.”

With tools from the 1960s

Behind the charm and nostalgia, the work is anything but easy. “They’re tough machines. You need experience. There are no proper manuals — just a few misleading videos online. The technology from the ‘50s, ‘60s and ‘70s has nothing to do with what we see today. Modern garages work with diagnostics and computers. Not here. We still use tools from the 1960s. I’ve added a few modern ones, but the way I repair is the same as it was decades ago. It’s all hands-on,” says Tommy.

“A Vespa is a living organism. Most of my customers stay the whole time while I work on theirs. They won’t let me touch it unless they’re present. They want to see it from the moment it’s stripped to the moment it’s finished. Some even help with the repairs — just to feel like part of the process.”

When asked if he’s worried someone might “steal his trade,” he shakes his head: “Quite the opposite. It would be better if they learned how to maintain them. Then they wouldn’t call me all the time. When you love something, you want to pass it on — not keep it to yourself.”

When the conversation turns to design, Chrysostomos becomes animated. “Japanese bikes are simple. The Italians, when they made the Vespa, would take you from point A to B with 50 turns in between. It’s not practical — it’s fussy. But that’s the beauty of the Vespa: the quirks, the angles, the style. That’s why it stayed timeless. From 1956 to 1990, the design hardly changed. They kept their identity.”

“Neglecting maintenance is the same as abandonment,” he confesses. Just then, the afternoon stillness is broken. A young man revs up a Vespa Primavera and vanishes into the alley, the engine screaming like new. But the style — that, it seems, will never fade.

Fading trades in a changing neighbourhood

The garage is one of the last remaining in Old Nicosia. “Out of the five machine shops once in Chrysaliniotissa, I’m the only one left. This street used to be full of blacksmiths, carpenters, aluminium workers. They’re all shutting down. Tourists pass through, take photos, but traditional trades are dying out. The area’s being redeveloped — new flats, changed zoning. Sometimes, it makes more financial sense to rent a place out than to keep a trade alive.”

How does he see the profession in ten years? “I might not be working here anymore. Eventually, we’ll leave. Maybe my son will take over — but you need real grit. Young people don’t have the appetite for this kind of work. Manual trades are disappearing. Most craftsmen now are migrants from other countries.”

A Vespa from Trachonas

What about the most difficult Vespa he’s ever had to repair? “For me, there’s no such thing as a difficult repair. I’ve seen it all,” he says. Still, one story stands out in his mind.

“The Vespa of Andreas from Trachonas. He managed to flee the village on the day the Turks invaded. He got his wife and their 16-month-old baby on the bike and drove through the chaos, as the National Guard fought a hopeless, betrayed battle against the invasion. The bike took a bullet. We restored it years later, but the hole is still there.”