Voice Accross

A cautious but unmistakable significant opening has emerged on the Cyprus front, as Turkish Cypriot leader Tufan Erhürman and Greek Cypriot leader Nikos Christodoulides completed their first substantive get-together in eight years under United Nations auspices on Wednesday, 20 November.

Excluding informal receptions, social events and UN-hosted 5+1 gatherings, the island’s two community leaders had not sat down together since the June 2017 Crans-Montana collapse, when the Greek Cypriot delegation walked out and the most advanced peace effort in decades unravelled overnight.

Against this historical backdrop, Wednesday’s meeting, cautious, controlled and largely exploratory, carries significance far beyond its modest choreography.

Leadership in transition

Erhürman, elected 19 October and sworn in on 24 October, entered the meeting not as a newly crowned leader buoyed by campaign slogans, but as a president who has already:

-

completed his first contacts with Ankara,

-

begun shaping his negotiation team, and

-

started signalling a more process-oriented, structured approach than seen in recent years.

By late November, Turkish Cypriot expectations had matured beyond celebratory optimism. What Wednesday delivered was the first serious reality test of the new leadership’s approach.

Signs by Holguín

Equally important, but less visible to the public, is the adjustment in the UN’s calendar.

UN Secretary-General’s Personal Envoy María Ángela Holguín Cuéllar had originally planned a regional tour to Cyprus, Türkiye and Greece between 3–11 November. That timetable was revised.

At Erhürman’s request, Holguín postponed her arrival in Cyprus to 4 December.

There are likely two parallel needs behind this request:

Deep consultation with Türkiye, not merely protocol-level talks in Ankara, but a thorough coordination exercise on methodology, red lines and expectations for a potential new round.

Serious preparation, reviewing the archive, including the Crans-Montana discussions, examining convergences and divergences line by line, and refining his four-pillar negotiating methodology into a coherent, documented proposal rather than an electoral talking point.

Holguín’s willingness to adapt her schedule suggests the UN acknowledges that unprepared, atmosphere-only meetings will not break a decade-long deadlock. The new timeline now offers a structured sequence leading into December.

The 20 November meeting

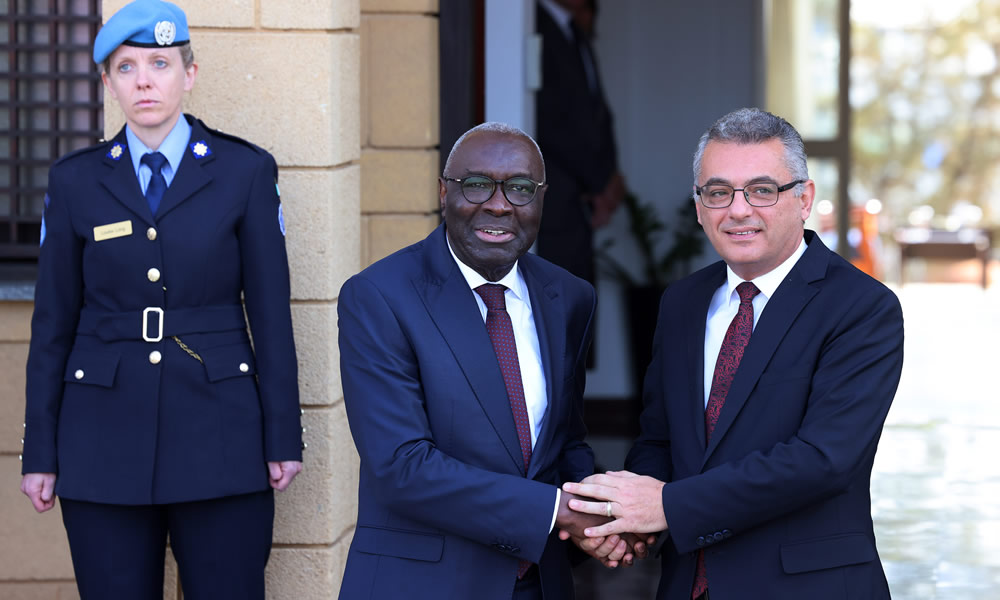

The meeting took place at the residence of the UN Secretary-General’s Special Representative Khassim Diagne, within the Nicosia buffer zone.

Erhürman arrived with undersecretary and incoming negotiator Mehmet Dânâ. Christodoulides came with chief negotiator Menelaos Menelaou. Holguín joined via videoconference from Lima, underscoring her direct involvement in the preparatory phase.

Diagne welcomed both leaders, posed for the obligatory handshake, and then withdrew, fulfilling the UN’s intention that this be a leader-to-leader introductory exchange, not an over-engineered negotiation round.

The meeting lasted around 85 minutes, including a 15-minute private discussion between the leaders.

UN: A roadmap, not an announcement

After the meeting, the first official word came from the United Nations.

The statement confirmed that:

-

Holguín will meet Erhürman on 5 December,

-

Christodoulides on 6 December, and

-

a joint trilateral meeting will follow during her stay.

Both leaders expressed that they “look forward” to this joint session and voiced readiness for a “wider informal meeting” later under the Secretary-General’s auspices.

They also instructed their representatives to start regular preparatory contacts immediately.

This is not a resumption of the formal, structured Crans-Montana-style negotiations. But it is the construction of a corridor towards that possibility.

Christodoulides' restrained optimism

Upon his return to the Presidential Palace, Christodoulides delivered a carefully calibrated briefing to the Greek Cypriot media. His tone was measured but consciously positive.

Pressed on whether Erhürman still supports a bizonal, bicommunal federation or whether he remains bound to his four methodological pillars, Christodoulides avoided confrontation and insisted these were questions best answered by Erhürman himself.

Instead, he highlighted:

-

the agreed 5–6 December Holguín meetings,

-

the start of negotiator-level preparations, and

-

the upcoming visit of EU Special Representative Johannes Hahn later in December.

He confirmed that confidence-building measures, crossing points and Greek Cypriot property issues were raised, but said it would be inappropriate, and contrary to mutual understanding, to divulge details at this stage.

Erhürman: Creating a solution atmosphere

Erhürman, in his press conference at the Turkish Cypriot Presidency later the same morning, called the meeting atmosphere “sincere and positive”.

He emphasised that:

-

communication channels will be kept open,

-

representatives will meet regularly with full authority, and

-

he remains committed to a structured, result-oriented sequence leading into and beyond Holguín’s December visit.

Erhürman reiterated that the desired solution atmosphere does not yet exist, and both sides share responsibility to construct it.

A 10-point package

Erhürman presented a 10-point package designed to build trust and functionality ahead of any formal talks. This includes:

-

citizenship rights for children from mixed marriages,

-

opening new crossing points,

-

removing bureaucratic barriers in Green Line trade,

-

resolving delayed contracts for halloumi producers,

-

creating a communication line between security forces, and

-

a symbolic initiative: both leaders attending the start of road-widening works in the buffer zone.

These are practical steps with immediate human impact, the kind of measures long needed alongside political dialogue.

Four pillars: From rhetoric to structure

For the first time at official level, Erhürman also shared his four-pillar methodology with both the UN and the Greek Cypriot leader.

These pillars, centred on timelines, guarantees against inconclusive withdrawal, political equality, and structured methodology, are intended to prevent the open-ended, circular talks that characterised earlier rounds.

Erhürman presents them not as preconditions, but as the distilled lessons of decades of failure.

Prospects: A narrow but real window

What does the 20 November meeting mean for Cyprus?

-

The UN has regained architectural control. The sequence of 5–6 December meetings, the planned trilateral, and the possibility of a wider informal gathering constitute the clearest UN-driven structure since 2017.

-

The EU is stepping back into relevance. With the Greek Cypriot-run Cyprus Republic preparing to take over the EU Council Presidency in January 2026, Brussels sees Cyprus not as a frozen conflict but as a strategic axis in its Türkiye policy.

-

Both leaders avoided early confrontation. Their public messages were controlled, cautious and constructive.

The Cyprus problem is not suddenly soluble. The core divergences remain sharp:

-

The Greek Cypriot side insists negotiations must resume from where they stopped in Crans-Montana.

-

The Turkish Cypriot side insists on a new methodology, guarantees and recognition of political equality as a non-negotiable foundation.

Yet for the first time since June 2017, the leaders have met formally. For the first time in years, though rather short for now, the UN has outlined a structured path. For the first time in a decade, both sides are signalling willingness to test whether a results-focused process can be constructed.

This may not yet be a breakthrough. But it is unmistakably the reopening of a diplomatic corridor long thought abandoned.

Whether this corridor becomes a road or another cul-de-sac will depend on Holguín’s arrival on 4 December, and on whether both leaders are ready to turn preparatory atmospherics into negotiating substance.

A new era for Cyprus peacemaking has not begun. But for the first time in eight years, it may finally be possible.