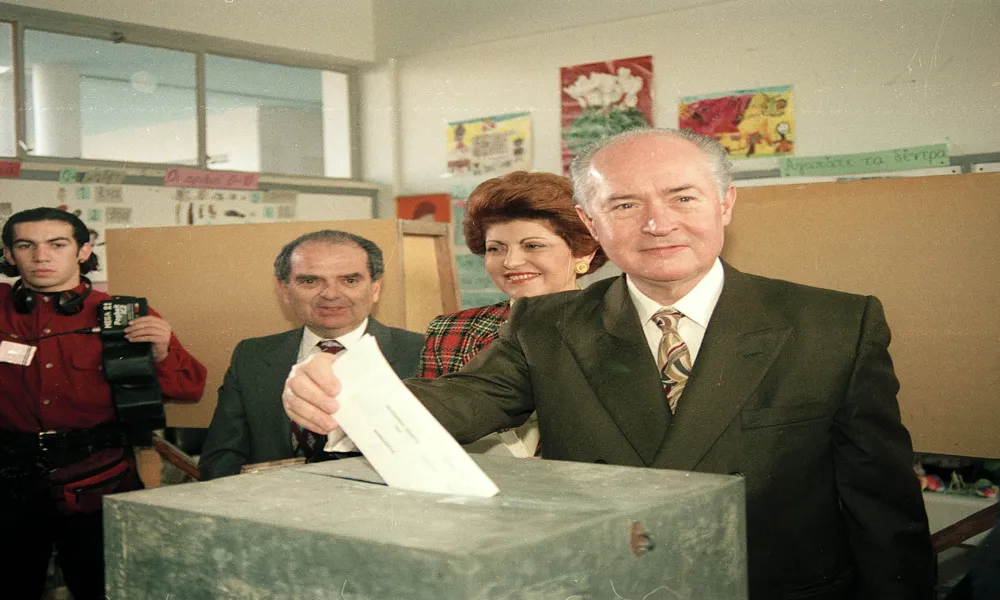

Many celebrated when George Vassiliou failed to secure a second presidential term in the 1993 elections. On one level, it was his occasional air of arrogance, the confidence of a self-made businessman that was unprecedented in Cyprus’ political culture. On another, it was the changes he introduced between 1988 and 1993, reforms that departed sharply from established practices and unsettled the country’s old political order, particularly its entrenched methods of exercising power.

Under both Archbishop Makarios and Spyros Kyprianou, governance had been deeply clientelist, narrowly patriotic and economically oligarchic. Power was concentrated. The governing circle controlled public-sector appointments, the handling of the Cyprus problem, the allocation of contracts, and the distribution of wealth through tourism and land-use decisions, often driven by pre-arranged rezoning that transformed land values overnight.

Against this backdrop, the election of Glafkos Clerides in 1993 was seen by many as the correction of a long-standing injustice. After decades in public life, Clerides, they argued, had earned his turn. Instead, Cyprus had first experienced the “parachutist” presidency of Vassiliou.

In military terms, a parachute drop is a form of unconventional warfare: it disrupts the battlefield instantly, overturning formations, balances and firepower. That is how Vassiliou’s election functioned politically. But the plan did not hold. As actor Alexis Galanos once quipped, Vassiliou “ran out of fuel”, and in 1993 he lost. What followed after Clerides’ two terms, however, proved far more consequential.

A shift in political culture

When Vassiliou was elected in 1988, Cyprus did not transform overnight. But something deeper began to change: how politics was conducted. The tone, the language, the strategic thinking, and above all the sense of what was possible.

In a political environment dominated by parties, slogans and rigid national certainties, Vassiliou was an unconventional figure. He did not speak like a professional politician, did not lead a traditional faction, and never invested in popularity. What he brought instead was something rarer: political realism, stripped of theatrical excess.

Breaking the party monopoly

Vassiliou was the first president to break, in practice, the monopoly of the traditional parties of power. For the first time, large segments of society saw that a technocrat, a figure from business with international experience, could reach the pinnacle of the political system.

This opened a path that then seemed improbable and today feels self-evident: the political legitimacy of independence from party machines. His election sent a clear message that the presidency was not the exclusive preserve of the party establishment. He did not dismantle patronage, nor did he sideline AKEL, which supported him. Instead, patronage was redistributed across party lines, with AKEL gradually securing the share it was entitled to.

The Cyprus problem without slogans

Perhaps Vassiliou’s most significant rupture came on the Cyprus problem. Not because he solved it, but because he changed how it was discussed.

He moved away from grandiose rhetoric and cost-free patriotism, and spoke openly about a bizonal, bicommunal federation, placing the Ghali Set of Ideas on the table; about necessary compromises, including political equality for Turkish Cypriots, while clarifying that this did not mean numerical equality; and about a solution that would function in practice, not merely satisfy the Greek Cypriot national narrative.

For the first time, a president spoke without fear of the political cost of realism. That is precisely why he paid the price in 1993.

Europe as strategy

Cyprus’ European trajectory did not emerge on paper under Vassiliou. Initially hesitant, mindful of Turkish Cypriot reactions, he came to see Europe as more than an economic union or a diplomatic shield, but as a framework of institutions, rules and the rule of law.

EU membership was treated as an instrument of stability and a potential pathway to a settlement, not as a national trophy. In a gesture of political maturity, Vassiliou harboured no resentment toward Clerides or DISY and later served as chief negotiator for EU accession. It was Clerides who led Cyprus to the Copenhagen Summit of December 2003, where accession was decided, but Vassiliou’s contribution to that path was substantial.

Governance without bombast

Vassiliou governed with a technocratic mindset, focusing on the economy, public administration and state functionality. He was communicative and effective in conveying his message. Even Rauf Denktaş acknowledged his skills, once remarking that Vassiliou was so adept at communication and marketing that he could “sell a refrigerator to an Eskimo”.

In essence, he introduced a political outlook that today would be described as European normality, but at the time felt alien.

A different political ethos

Vassiliou’s most enduring legacy lies not in legislation or agreements, but in political ethos. He maintained a low tone, accepted disagreement, engaged with opponents, and avoided nationalist rhetoric.

When he first said that a Cyprus settlement could turn the island into the Singapore of the Eastern Mediterranean, he was accused of anti-Hellenism. He persisted, patiently explaining his vision. Today, many acknowledge that Cyprus should long ago have become a regional services hub, rather than a peripheral player in Middle Eastern instability.

The legacy of a premature politics

Vassiliou was, in many ways, a president ahead of his time. Ideas once dismissed as naive or dangerous are now mainstream. In 1993, he won an extraordinary 44.15 percent in the first round, with 157,027 votes, far ahead of Clerides’ 36.74 percent. That result, however, fed an inexplicable arrogance. His public call for Clerides not to contest the second round triggered the reflexes of the old party system, which reasserted itself. Clerides won narrowly with 50.30 percent.

The problem was not Clerides’ election, as he shared much of Vassiliou’s thinking. The deeper issue was that it allowed the old political guard to regroup. What followed were the presidencies of Tassos Papadopoulos, Demetris Christofias and Nicos Anastasiades. Had Vassiliou won in 1993, party renewal would have been unavoidable, and that generation of old-style leaders might never have emerged.

What remains of George Vassiliou is a political legacy that continues to resonate in a Cyprus still torn between realism and illusion. It is a legacy of courage, restraint and foresight.

Thank you, Mr President, and farewell.