First published in the United States on this day in 1950, Nineteen Eighty-Four introduced a chilling vision of surveillance, propaganda and authoritarian power that continues to shape political language and democratic anxieties more than seven decades later.

When Nineteen Eighty-Four reached American readers on January 21, 1950, it arrived not simply as a work of fiction but as a provocation. In the shadow of World War II, amid the rise of Cold War paranoia and expanding state power, the novel offered a bleak mirror of what the modern world might become if authority went unchecked and truth itself was manipulated.

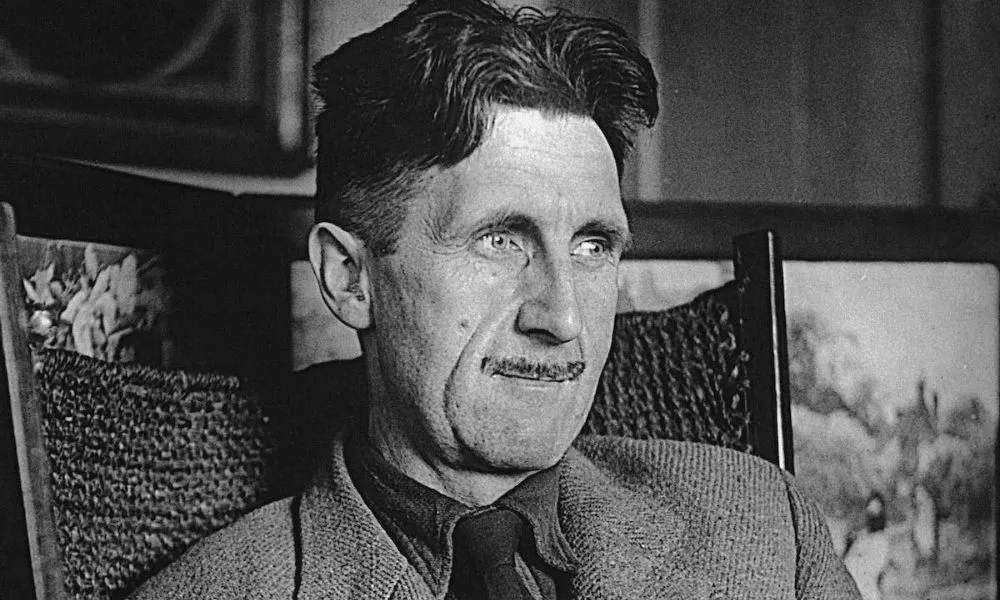

Its author, George Orwell, had already established himself as one of the sharpest political minds of his generation. With Nineteen Eighty-Four, he produced a final, uncompromising warning.

The world Orwell imagined

Set in the totalitarian superstate of Oceania, the novel follows Winston Smith, a minor bureaucrat working at the Ministry of Truth, where history is constantly rewritten to suit the ruling Party. Surveillance is omnipresent, language is weaponised, and independent thought is treated as a crime.

At the centre of this system stands Big Brother, a figure whose image dominates public life but whose existence remains ambiguous. Power is not only enforced through violence, but through the careful erosion of language, memory and reality itself.

Concepts introduced in the novel have since become cultural shorthand. “Big Brother” now universally signifies intrusive surveillance. “Thoughtcrime” describes the criminalisation of dissenting ideas. “Doublethink” captures the mental gymnastics required to accept two contradictory truths at once.

Orwell’s life and political urgency

Orwell, born Eric Arthur Blair in 1903, was shaped by direct experience of power and injustice. He served as a colonial police officer in Burma, an experience that fuelled his hatred of imperialism. Later, he fought in the Spanish Civil War, where he witnessed first-hand the brutality, propaganda and internal purges that defined totalitarian movements.

These experiences informed his writing. Orwell rejected political extremism of all kinds, believing that authoritarianism could emerge from both the right and the left. His commitment was not to ideology, but to intellectual honesty, clarity of language and individual freedom.

By the time he completed Nineteen Eighty-Four, Orwell was gravely ill with tuberculosis. The novel was published just months before his death in January 1950, giving it the weight of a final testament.

Language as a tool of control

One of the novel’s most enduring contributions is its focus on language. Through “Newspeak”, the Party systematically reduces vocabulary in order to limit the range of thought itself. If words disappear, so do the ideas they represent.

This insight has proven remarkably resilient. Orwell’s warnings about political language being used to “make lies sound truthful and murder respectable” continue to resonate in debates about spin, disinformation and media manipulation.

In an era of soundbites, algorithms and strategic messaging, Orwell’s insistence that language shapes reality feels less literary and more diagnostic.

From Cold War fiction to modern anxiety

Initially read through the lens of Soviet totalitarianism, Nineteen Eighty-Four has since outgrown any single historical context. Its relevance has expanded alongside technological change, particularly in discussions about mass surveillance, data collection and state-corporate power.

The novel is now frequently cited in debates about privacy, digital monitoring and the erosion of civil liberties, not because it predicted specific technologies, but because it understood how power adapts.

Orwell’s genius lay in recognising that control does not always arrive with boots and batons. Sometimes, it arrives quietly, disguised as security, efficiency or even comfort.

A book that refuses to age

More than seventy years after its publication in the United States, Nineteen Eighty-Four remains unsettling precisely because it never feels safely historical. Each generation finds new reasons to recognise itself in its pages.

On this day, the novel stands not as a relic of Cold War fears, but as a living text, continually reread as societies renegotiate the balance between power, truth and freedom. Orwell’s warning, it seems, was never meant for just one moment in time.