When the first book in the Bridgerton series was published in 2000, its identity was unmistakable. Pink and purple cover, looping typography, compact size and flimsy paper. It was a mass market paperback, designed to be cheap, portable and disposable. The kind of book sold on wire racks in airports, supermarkets and pharmacies for a few dollars.

Those racks have almost vanished. And with them, so has the format.

After nearly a century of dominance, the mass market paperback is edging toward extinction. Sales have been declining for years, squeezed by e-books, audiobooks and, increasingly, by larger and more expensive print formats such as trade paperbacks and hardcovers. In 2025, ReaderLink, the largest distributor supplying books to airports, pharmacies and big-box retailers in the United States, announced it would stop carrying mass market paperbacks altogether.

“You can still find them in some places,” said Ivan Held, president of Putnam, Dutton and Berkley. “But as a format, it’s pretty much over.”

Built for access, not durability

The modern paperback was born in the mid-1930s, when British publisher Allen Lane launched Penguin Books after being frustrated by the lack of affordable reading material at a railway station. His idea was radical: compact books, clearly branded, sold outside bookstores and priced no higher than a packet of cigarettes.

It was a publishing revolution. Paperbacks could be slipped into a pocket or handbag, carried on commutes and read anywhere. But affordability came at a cost. Pages were glued rather than sewn, covers detached easily, and libraries largely avoided them due to their fragility.

What they lacked in durability, they made up for in reach. By the late 1930s and 1940s, mass market paperbacks flooded supermarkets, drugstores and bus stations, distributed alongside magazines and confectionery. During the Second World War, millions were printed in special horizontal formats for soldiers, designed to fit into military uniforms.

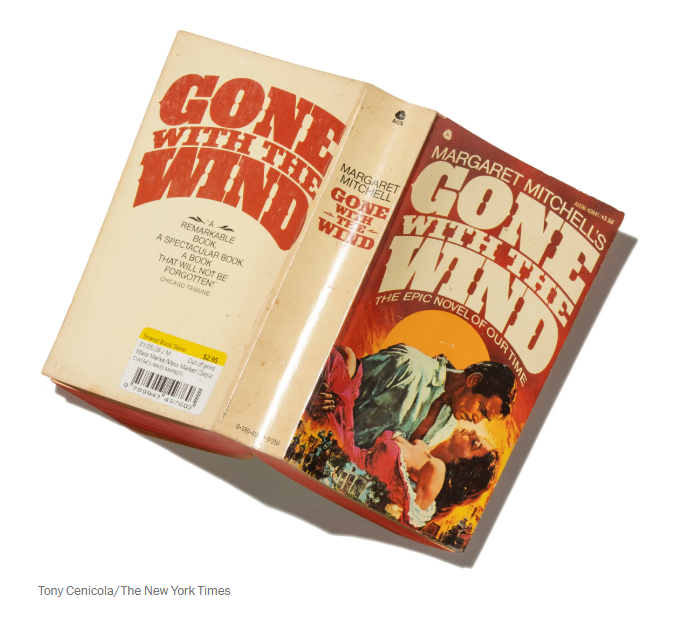

By the mid-20th century, mass market paperbacks, often referred to as “pulps”, were cultural fixtures. Westerns, thrillers, romance and even classics were sold with lurid, provocative covers. A successful mass market title could sell millions, far outpacing hardcover editions.

The economics no longer add up

That model has collapsed. According to Circana BookScan, mass market sales in the United States fell from around 103 million copies in 2006 to fewer than 18 million last year. The number of titles declined more slowly, indicating that publishers did not abandon the format first. Readers did.

Romance readers, once the backbone of mass market sales, were among the earliest adopters of e-readers. Digital formats offered lower prices, instant access and storage for thousands of titles. At the same time, readers proved increasingly willing to pay more for trade paperbacks and deluxe hardcovers.

“There is only about a 30-cent difference in production cost between a mass market and a trade paperback,” said Dennis Abboud, chief executive of ReaderLink. “But the trade version can sell for six dollars more.”

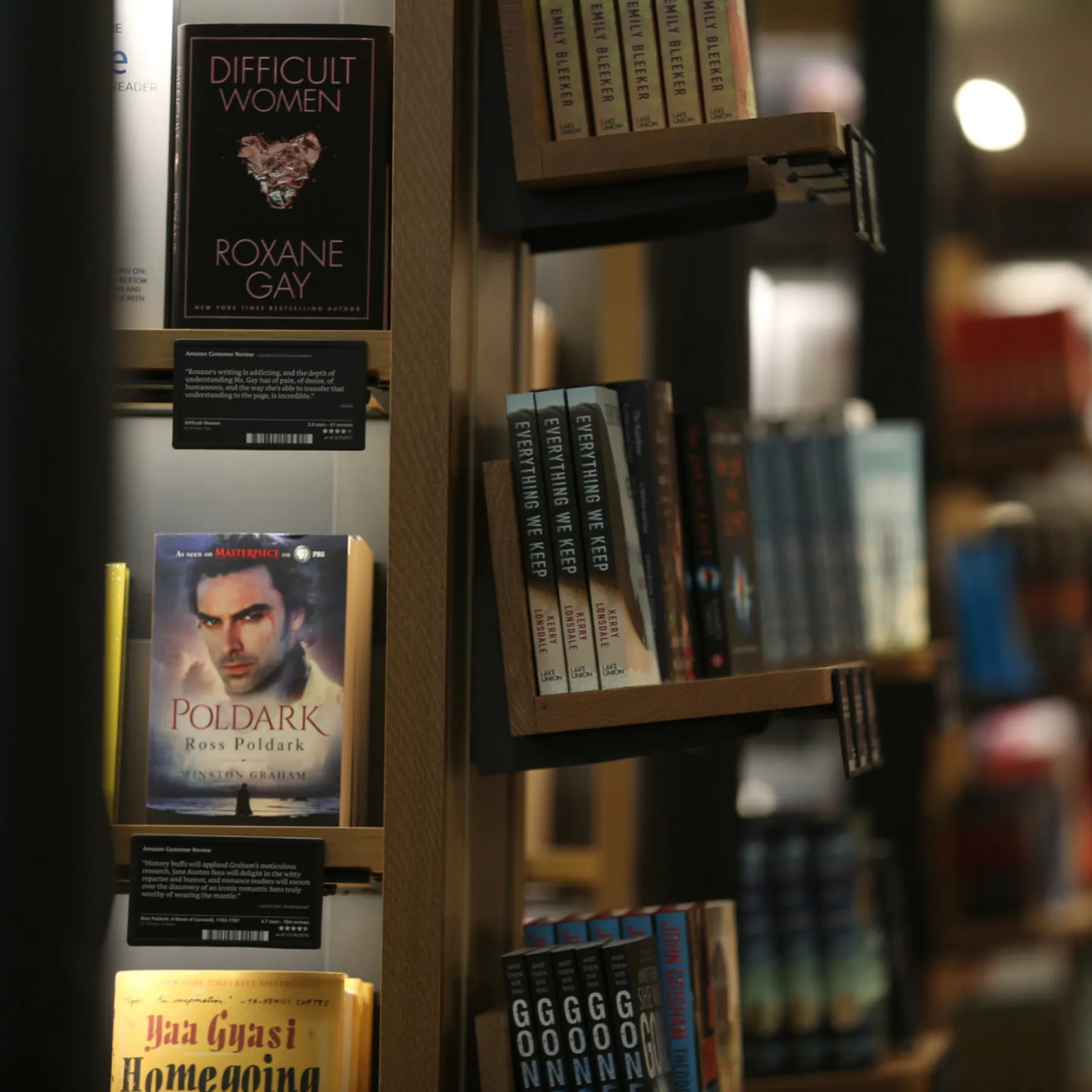

Retailers followed consumer behaviour. Hudson, which operates over 1,000 travel-hub stores across North America, phased mass market paperbacks out of convenience locations and stopped carrying them entirely in 2025. Dedicated bookstore branches now stock only limited selections.

Even Bridgerton is no longer printed in mass market format. Once remaining stock is sold, it will not be replenished.

What survives and why

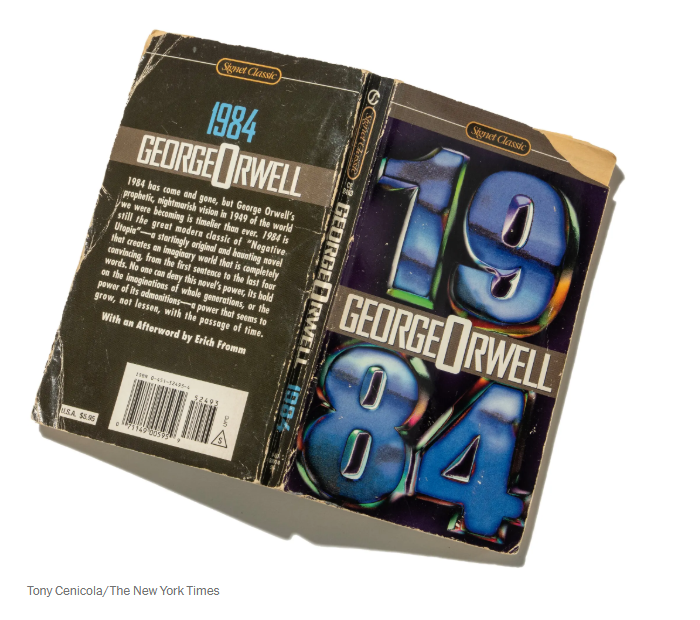

Some mass market titles persist, mainly where cost remains decisive. Schools continue to buy inexpensive editions of classics such as 1984 and To Kill a Mockingbird. In 2025 alone, more than 210,000 mass market copies of A Raisin in the Sun were shipped in the US.

The format also retains nostalgic and collector value. Second-hand bookstores still sell thousands of used mass markets each year, sometimes fetching high prices among collectors.

For writers, the format once represented access and opportunity. Stephen King has repeatedly credited paperback sales with enabling him to write full-time after his debut novel Carrie sold its paperback rights for $400,000. That pathway is now largely closed.

The end of a reading culture

The decline of the mass market paperback is not simply about format. It marks the end of a reading culture built on physical accessibility rather than aesthetic value. These were books meant to be handled, folded, lent and eventually discarded.

Younger readers today may still discover old mass market copies in second-hand bins, yellowed and brittle, relics of a time when books were designed to travel easily between hands rather than shelves.

What replaces them is not less reading, but different reading. More digital, more curated, more expensive. The paperback that once democratised literature has quietly stepped aside, leaving behind a publishing world that is sleeker, costlier and far more selective about who it serves.

Source: The New York Times