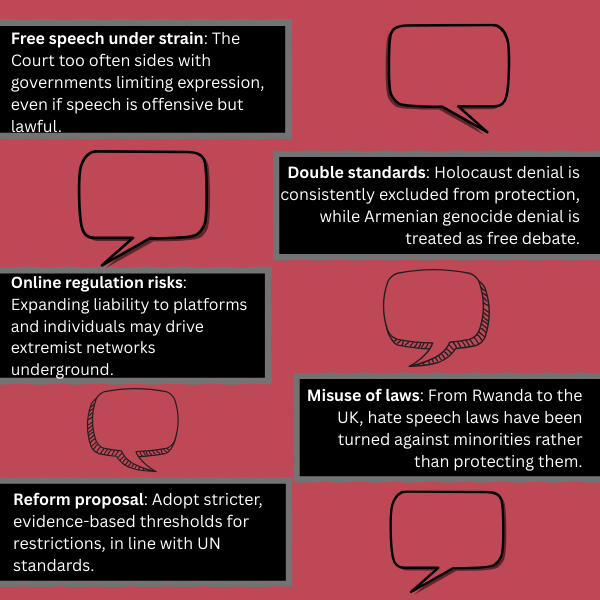

Natalie Alkiviadou, Senior Research Fellow at the Future of Free Speech at Vanderbilt University (USA), argues in her new book that the European Court of Human Rights has become too restrictive on freedom of expression, often backing governments in silencing speech that is merely offensive.

Alkiviadou, an expert on free expression, hate speech and the far-right, says bans and censorship do not reduce prejudice or violence. Instead, she contends, open debate, education, and counter-speech are stronger tools against racism, homophobia, transphobia and other forms of intolerance.

Highlighting inconsistencies in the Court’s rulings, from Holocaust denial to Armenian genocide denial, and warning against the unintended consequences of over-regulating online platforms, she stresses that hate speech laws are often misused by those in power and risk harming the minorities they aim to protect. Her central call is for the Court to adopt stricter, evidence-based thresholds for restricting speech, aligning its approach with international human rights standards.

Hate Speech Laws at a Crossroads

For Natalie Alkiviadou, the antidote to hatred is not less speech, but more. “Open debate, counter-speech, education and dialogue are far stronger antidotes to racism, homophobia and transphobia than bans or censorship,” she says. What unsettles her is how diluted freedom of expression has become across Europe. “As societies fight prejudice, there is an equally urgent need to protect free speech. These two objectives should go hand in hand.”

Her concern is not abstract. Decades of strict hate speech enforcement in Germany, she notes, did not prevent either the rise of the Nazis during the Weimar Republic or the more recent growth of the far-right Alternative for Germany. “Hate speech laws often promise protection, but the evidence suggests they do not actually reduce intolerance or violence,” she argues.

Central to her analysis is the role of the European Court of Human Rights, which she says has increasingly sided with governments in restricting expression. “When I say the Court has been too restrictive, I mean it often upholds convictions even where the speech is merely offensive or prejudicial,” Alkiviadou explains.

One case stands out: that of a Belgian politician who distributed leaflets warning against the “Islamisation of Belgium” and describing refugee centres as a public nuisance. The Court upheld his conviction and barred him from political office for ten years. “Crucially, it said that defamation, ridicule or insults directed at groups could be enough to justify restrictions,” Alkiviadou says. “That sets a very low bar and undermines the Court’s own principle that free speech protects not only agreeable ideas but also those that shock, offend or disturb.”

Equally troubling, she continues, is the Court’s inconsistency in dealing with genocide denial. Holocaust denial is systematically excluded from protection, while denial of the Armenian genocide has been treated as legitimate debate. “This double standard creates a hierarchy of suffering: some atrocities are treated as beyond discussion, while others are left to contestation,” she warns. “Such inconsistency risks privileging certain narratives of history over others and undermines the Court’s credibility as a neutral guardian of free expression.”

The challenges are magnified online, where hate speech laws that once targeted newspapers or rallies are now applied to social media platforms. The Court has reinforced this shift, holding intermediaries and even individuals liable for user-generated content. In Delfi v Estonia, a news site was held responsible for offensive reader comments; in Sanchez v France, a politician was convicted not for his own words but for failing to remove comments left under his Facebook post.

“These rulings expand the duties and responsibilities of free speech to include both platforms and individuals, effectively turning them into gatekeepers,” Alkiviadou says. Yet, she cautions, such measures can backfire. Research shows that when extremist figures are banned from mainstream platforms, many regroup on less moderated channels such as Telegram, where their networks often become more extreme. “Instead of silencing harmful ideas, heavy-handed restrictions can drive them underground, making them harder to monitor and potentially more dangerous,” she adds. “And in practice, most of the speech removed by platforms is legal.”

Her book also warns of how hate speech laws, often drafted in vague terms, can be misused by those in power. Rwanda offers a stark example. After the 1994 genocide, laws banning “divisionism” and “genocide denial” were passed with the stated aim of preventing future atrocities. In reality, Alkiviadou says, they have been used to prosecute journalists and opposition figures who questioned the government’s narrative. “Far from fostering unity, these laws have silenced dissent and entrenched divisions,” she says.

Europe has its own cautionary tale. As highlighted by Mchangama and Strossen, because hate speech laws are often vague and overly broad, even well-intentioned hate speech laws tend to reflect the biases of those in power. The UK’s landmark 1965 Race Relations Act, which outlawed incitement to racial hatred, was first used against a Black man. In the years that followed, several other Black Britons, including leaders of the Black Liberation Movement, were also targeted for allegedly directing “anti-white hatred.” “Ironically, laws meant to protect minorities ended up being used against them,” she notes.

So what should change? Alkiviadou believes the Court needs to root its rulings in empirical evidence rather than assumptions. “Too often, judgments rest on abstract claims that offensive words will inevitably cause harm,” she says. “Governments should only be allowed to restrict expression where there is evidence of a genuine threat, in line with international human rights standards such as the UN’s Rabat Plan of Action.”

While she personally views the U.S. First Amendment as the strongest model for protecting speech, she is pragmatic about Europe’s limits. “I don’t propose the First Amendment for Europe but the Court can, and should, adopt stricter, evidence-based thresholds to ensure its jurisprudence is coherent, legitimate and effective.”

At the Future of Free Speech based at Vanderbilt University where she works, this is the mission: “to reaffirm freedom of expression as the foundation of democratic societies through research, advocacy and outreach.” The project studies why free speech is in decline, tests whether restrictions are based on

real or imagined harms and defends international standards against authoritarian erosion. “Equally important,” Alkiviadou adds, “is providing activists, policymakers and academics with the tools and evidence they need to resist censorship and build a resilient global culture of free expression.”

About the Author

Natalie Alkiviadou holds a PhD in Law from the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam and has published four monographs with Routledge on hate speech, free speech and the far-right. She has published widely in peer-reviewed journals, worked with civil society on human rights education, and serves on advisory boards of initiatives promoting democratic literacy and free expression.