Plastic crates replaced wicker for farm produce. Plastic bags replaced shopping baskets. And as daily life shifted, so did what people needed - quietly pushing a once-essential craft towards the margins.

In Mesogi, Paphos, a village whose name was synonymous for decades with baskets and large wicker hampers, basket-weaving was never just a craft. It was a livelihood, a rhythm of life, and a local economy. Through the memories of 87-year-old retired teacher Onisiforos Neofytou, the story unfolds of a home-based industry that supported families, clothed children, paid for studies, and kept the village afloat. Today, that craft is fading, leaving behind names, stories, and a shared sense of loss.

A Sunday Morning In Mesogi

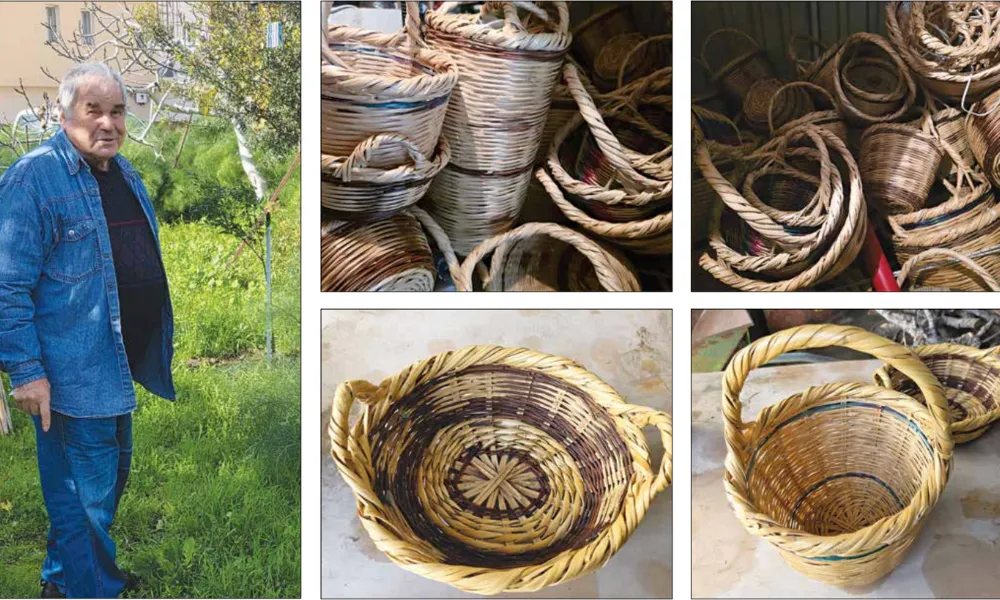

Our meeting with Onisiforos Neofytou and his wife Anna was set for a Sunday morning at their home in Mesogi. Neofytou began basket-weaving at the age of 12 and still remembers selling his first pieces while he was barely more than a child.

He speaks with emotion - and sadness - about an art that is disappearing. It is, he says, the craft that “fed, clothed and educated so many families”. A craft that sustained mothers and children.

After a forty-year career in education, Neofytou returned to his village. Only a handful of basket-weavers remain, working mainly when a specific order comes in. These days, he says, most pieces are fruit baskets, bread baskets, and decorative baskets for hotels and venues. What has largely disappeared are the large-scale wicker hampers once used for harvesting and transporting carobs, grapes, olives and other produce, as well as shopping baskets, laundry panniers, and baskets used by fishermen. Everything, he explains, was replaced by plastic.

Materials, Colour, And The Old Techniques

The main raw material remains reed (cane). For decorative elements - the “ploumia” (ornamental patterns) - artisans use dyed “limia”. To dye them, a green or reddish powdered malachite is dissolved in boiling water. The limia are dipped into the mixture and take on the colour. Neofytou notes that “ploathkia” - materials that are easy to weave and add firmness and beauty - are now rarely used.

The Story Of Basket-Weaving In Mesogi

Neofytou says basket-weaving in Mesogi dates back far, because these items were essential to daily life. Exactly when the first baskets were made is unknown, as there are no written records or archaeological findings.

The only testimony comes from the memories of the village’s elders, including people such as Yiannis “tou Klokkarou”, his brother Pavlis, Omiris “tou Gerakli”, Yiortanis “tou Ketikki”, Nikolas “tou Chatzipanagi”, and others of their generation.

The earliest baskets are estimated to have been made in the late 19th to early 20th century.

At first, the craft was practised mainly by men, with women assisting. Among the families of early makers were those of Koutsogiorgis “tou Appiiotou”, Themistoklis “tou Piskopou”, Manoilis, Tooulis “tou Rouchouna”, and Palaousios. Across Cyprus, Mesogi became known as “the village of baskets.”

The Women Who Held The Village Together

With deep emotion, Neofytou speaks about the women basket-weavers who are no longer alive. Many built family workshops with the help of their children - and sometimes their husbands - producing anything that could be woven from reeds and ploathkia.

Remembering them, he says, feels like a memorial and an act of gratitude. Their labour kept the village economy stable, provided dowries, educated children, and helped shape Mesogi into a progressive and respected community.

Today, active basket-weavers can be counted on one hand: Chrystalla Andreou Armefti, Maroula Charalambous, and Aristi Charalambous. Even more troubling, Neofytou says, is that the craft is no longer being passed on to younger generations.

What Mesogi Used To Make

The range of woven goods produced in Mesogi was vast, including:

- baskets of many sizes

- large wicker hampers for produce

- panniers

- “koukkourkes” for transporting poultry (long narrow baskets about 50–60cm in diameter and around two metres in length)

- “kokkoures” for transporting birdlime sticks and rods

- “tytokanies” for protecting cheeses and anari

- “tziimoi” (muzzles) for oxen and donkeys

- reed screens and woven cane shelters

Neofytou links the craft’s growth to Mesogi’s limited and less fertile agricultural land. Few residents were farmers, so the village sought other forms of work. A decisive factor was the presence of reed-beds along rivers and water-rich areas such as Dkyoσmies, Mana tou Nerou, Fonisissa, Varos and Vrysin.

Today, he says, many of these areas have become barren, with water sources drying up due to over-pumping.

His Own Beginning And The Social Life Of Weaving

Although basket-weaving began as a male occupation, women became the most skilled practitioners, and the craft ultimately passed into their hands. Men moved towards jobs with higher income: builders, tailors, carpenters, shoemakers, miners, and labourers.

Neofytou recalls how women gathered under massive terebinth trees and carob trees that once filled Mesogi - trees that no longer exist, he says, sacrificed to charcoal production and development.

They wove, gossiped, exchanged news, and found community. Often their thoughts drifted to husbands working away from home - in other towns and villages, in mines, and on roads. At times, the women broke into short folk couplets mourning loneliness.

Selling Baskets: Trade, Routes, And Barter

Before the 1950s, Neofytou says, buyers travelled to Mesogi to purchase or place orders with basket-makers they knew.

He remembers key homes near the main road (linking Paphos with Tsada, Polis Chrysochous and the wider countryside) acting as steady points of trade - including the houses of Aunt Kalodoti “tou Sovroni”, Chrystallou “tou Kasiouli”(wife of Uncle Spyros “tou Bazouka”), and Ermina “tis Loxantrous.”

Women traders sold not only their own work but also pieces bought from other village women.

Neofytou also remembers his parents loading their donkey with woven goods and taking them to villages and fairs. Trade was often based on barter: baskets exchanged for household provisions - legumes, olives, potatoes, cheeses, anari, trachanas, and anything Mesogi did not produce in sufficient quantities.

Land and wealth, he says, were concentrated in the hands of the few - the wealthy and moneylenders - while many survived on income from basket-weaving and day labour.

Today: A Craft In Decline

With the rise of plastic crates and bags, basket-weaving has slipped into decline. The remaining basket-weavers are few. Neofytou says efforts to keep the craft alive have produced limited results.

Some baskets are occasionally purchased by the Handicrafts Department in Nicosia. Hotels and leisure venues buy baskets for decoration. Tourists and local craft-lovers still purchase a few pieces. But the home-industry, he says, cannot be saved from its downward slide.

The basket-weavers who remain are loyal to tradition, trying “with nails and teeth” to keep the craft alive - even if, as he puts it, the profession is now “in intensive care”.

The art stands at the edge of forgetting, kept alive by memory, tired hands, and stories worth telling. With it, a form of knowledge is disappearing - passed down without books, only through watching, patience, and practice.

And yet, every basket that survives still carries the memory of a slower life - one tied closely to land, seasons, and the village’s old rhythm.