Only three years after the establishment of the Republic of Cyprus, the young independent state found itself experiencing the first major traumas of its existence. The events of December 1963, known today as the Bloody Christmas, were a result of a long trajectory of structural contradictions, historical fears and parallel strategies that developed both inside and outside the island.

Today, Sunday, Politis newspaper publishes its History Chronicle, an attempt to trace step by step how Cyprus reached division: from the complex Constitution of 1960, to the creation of the Turkish Cypriot TMT, the secret drafting of the Akritas Plan, the disagreements surrounding Makarios’s thirteen amendments and the final eruption of violence in December 1963.

1960: Birth and limitations

The architecture of the Constitution is often described as one of the most complex in the world. Greek Cypriots, about 78 percent of the population, and Turkish Cypriots, about 18 percent, were required to co-govern in a system with strict quotas, veto rights and separate administrative structures. Within this rigid system, the lack of trust between the two communities, already entrenched since the 1950s through the conflicting aims of EOKA and the Turkish Cypriot leadership, did not allow the smooth functioning of the state.

TMT & Akritas Plan

TMT (Türk Mukavemet Teşkilatı) was founded in 1958, two years before independence. TMT was a centrally organised, fully directed paramilitary structure with the direct involvement of Turkish officers.

From the Greek Cypriot side, the period 1960 to 1962 was marked by growing frustration with the functionality of the Constitution. Many senior officials believed that the Zurich London framework was unworkable in a state where the overwhelming majority felt trapped in a system of compulsory parity.

Makarios’ thirteen amendments: The political turning point

Daily friction between the two communities gradually increased. Issues such as taxation, separate municipalities, police transfers and even the operation of mixed patrols created constant tension. On 30 November 1963, President Makarios handed the Turkish Cypriot leaders a proposal for thirteen constitutional amendments. The changes aimed, according to him, to improve the functionality of the state. Among other things, they provided for:

• abolition of the vice president’s veto

• abolition of separate municipalities

• changes to taxation

• unification of the civil service

• the possibility of convening mixed armed units

For many Greek Cypriots, the thirteen amendments were necessary and reasonable. For Turkish Cypriots, however, they amounted to a revision of their constitutional equality. Their leadership rejected the proposals immediately. Turkey publicly condemned them, warning that any change to the Constitution would endanger the island’s balance.

Trust collapsed. The following weeks were filled with fear, rumours and preparations. On 30 November, the day after Makarios delivered his proposals to Fazıl Küçük, interviews with Küçük and Rauf Denktaş were published in a newspaper in Istanbul, in which they expressed their views on Makarios’s request for constitutional revision. In his interview, Rauf Denktaş stated that the leaders of the Greek community must abandon the adventure of self determination and union. They must embrace the current status and accept that the Turks are partners in this status. On the same day, President Makarios responded with a speech in favour of union, speaking of the unity of the Greek and Cypriot space, despite the fact that three years had passed since the signing of the Zurich London agreements.

Bloody Christmas

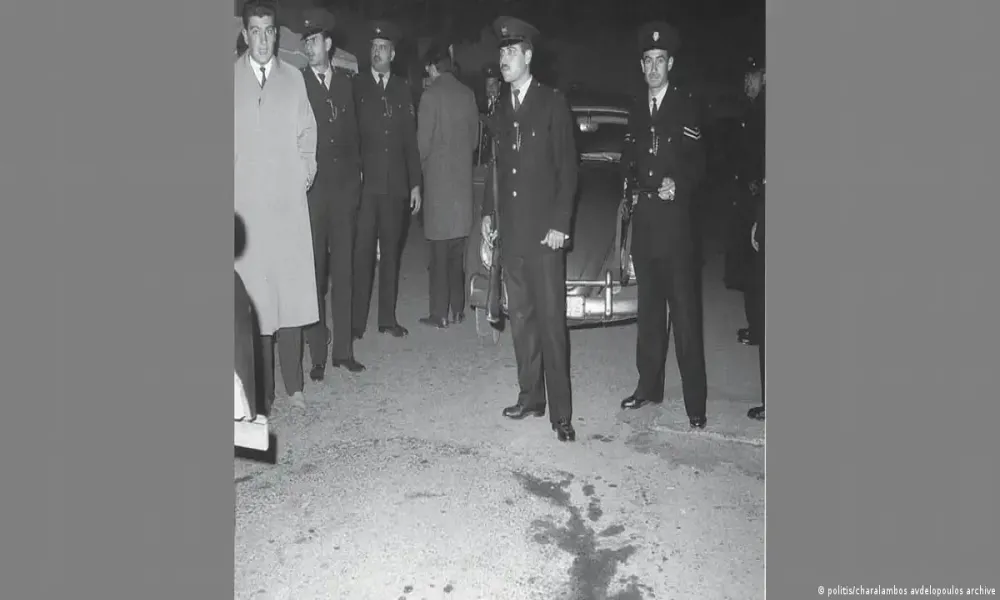

On the night of 21 December 1963, Greek Cypriot police officers stopped a car carrying Turkish Cypriots on Paphos Ermou Street in Nicosia, in a mixed area of high tension. The circumstances remain disputed, but the outcome was dramatic: an exchange of fire, panic and the death of two Turkish Cypriot women. The news acted as a detonator. Within hours, clashes broke out in Nicosia and spread to other mixed areas.

From 22 to 25 December, the capital turned into a battlefield. Greek Cypriot and Turkish Cypriot groups clashed in Omorphita, Ayios Kassianos, Koutsoventis, Kokkinias and many other mixed parts of the city. In the following days, the clashes widened. The incidents continued the next day as large numbers of Turkish Cypriots, many of them armed, roamed the streets of the old city uncontrollably. The initial appeals of President Makarios and Vice President Küçük were ignored and by the afternoon the clashes had spread to other neighbourhoods of the capital.

That December, because of the fighting, many Greek Cypriots became displaced, particularly in Neapolis and Ayios Dometios, who until then had lived in urban areas close to Turkish Cypriot neighbourhoods or in villages where Turkish Cypriots formed the majority. Many Turkish Cypriots also left urban areas in Nicosia such as Kaimakli.

Archbishop Makarios was later accused of committing a major error by submitting the proposal to amend the Constitution. On the other hand, there is serious evidence that the uprising of the Turkish Cypriots was planned and promoted by Ankara. In a much later interview in 1984, Rauf Denktaş admitted that TMT wanted to reignite the crisis and therefore placed bombs in Turkish mosques in order to blame the Greek Cypriots.

Green Line

On 23 December, the Turkish Cypriot ministers withdrew from the government. A few days later, an agreement was signed for the creation of the Green Line. The agreement, coordinated with Athens and Ankara, which marked the end of hostilities, was signed on 30 December 1963 in Nicosia by the British Colonial Secretary Duncan Sandys, President Makarios, Vice President Fazıl Küçük, the President of the House of Representatives Glafcos Clerides and the President of the Turkish Cypriot Communal Assembly Rauf Denktaş.

The task of marking the dividing line was assigned to British Major General Peter Young, who drew it on the map with a green pencil. This is why we know it today as the Green Line. Its purpose was to prevent escalation between Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots, and its policing was assigned to UN peacekeepers.

The Turkish Cypriot enclaves

This dividing line marked the beginning of the creation of Turkish Cypriot enclaves. Turkish Cypriot civil servants abandoned their posts and remained in the Turkish sector of Nicosia, as did Turkish Cypriot MPs and ministers. Over time, an embryonic Turkish Cypriot administration emerged in the Turkish sector. Free movement was restricted, as was communication between Greeks and Turks. Tension between the two communities eased significantly in 1968, when bicommunal talks began between Glafcos Clerides and Rauf Denktaş for the resolution of the Cyprus problem. On that occasion, Ledra and Ermou streets were opened to serve Turkish Cypriots working in the Greek Cypriot sector.

The crisis continued for months. In March 1964, the UN Security Council approved the creation of the UNFICYP peacekeeping force, which was deployed on the island and remains there to this day.

The events of 1963 should not seem as surprising. They were the result of a series of crises that were never decisively addressed. The crisis of those days opened the path to the gradual entrenchment of division and shaped the course of Cyprus for the next sixty years. History returns in every discussion of the Cyprus issue not as an exercise in nostalgia, but as a reminder of how fragile a political structure can be when trust between communities has collapsed and when the shadows of external actors remain heavy.