The received wisdom among Cyprus problem observers – and those inclined to games of chance – is that you never bet on a Cyprus solution. But since hope dies last, and the lesson of all conflicts is that ‘you keep building on failure until you achieve success’, a breakthrough is never far from the realm of possibility.

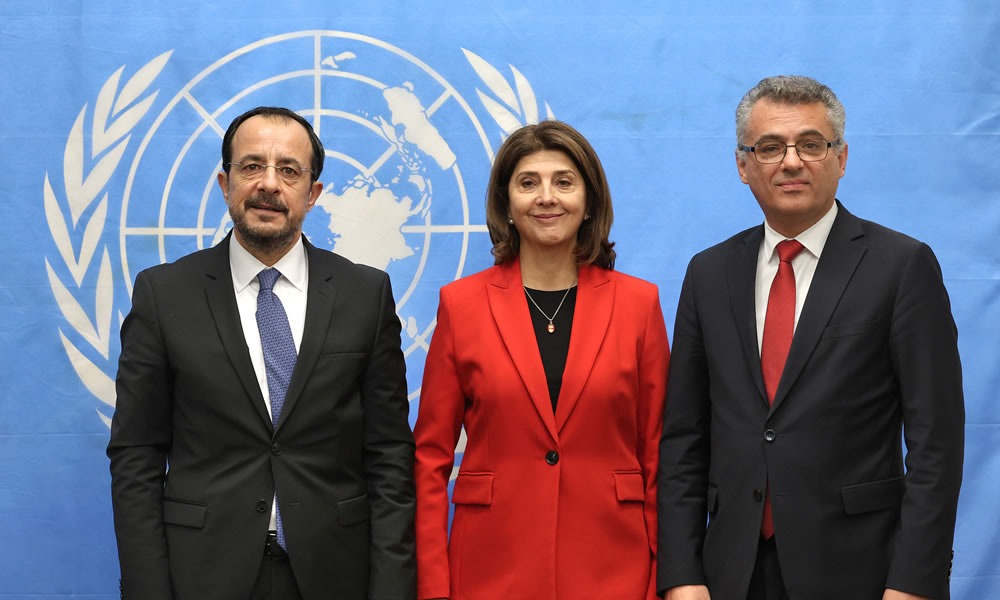

After UN Personal Envoy María Ángela Holguín Cuéllar indicated her return to the island was dependent upon a “specific step forward”, the onus is now on the leaders to find a way out of the quagmire. While Holguín’s position that serious talks could not be held until July rankled President Nikos Christodoulides, who considered it “laughable”, the UN Secretary-General gave her his full backing.

And so, Christodoulides and Tufan Erhürman meet again this Tuesday at the old Nicosia airport – without Holguín. It is clear the international community wants to see signs of progress, and since a resumption of talks is not currently on the cards, this needs to come in the form of confidence-building measures (CBMs).

At the same time, following decades of failed peace efforts that always adopt the same framework of top-down, non-inclusive negotiations that pursue a ‘big bang’ settlement from Day One, academics and analysts are increasingly exploring alternative options to fix what they consider to be a broken process.

So, how close are the leaders to moving forward either with small trust-building steps or with the essence of the matter – resuming peace negotiations after nine years of stagnancy. And how much would the leaderships embrace alternative approaches to the process?

Politis spoke with reliable sources from across the island to get a sense of how near or far the leaders are in changing the state of play.

Building trust or undermining confidence?

Presently, we have one side ready to resume talks from where they left off immediately, and the other saying they will not engage in another process doomed to failure that leaves them in a permanent state of limbo. The Turkish Cypriot leader wants to create an environment conducive to a settlement before embarking on a new round of talks.

This means agreeing and implementing trust-building measures on the one hand, while making tweaks to the negotiation process on the other, to facilitate success and prevent a return to the status quo, which the UN Secretary-General says – and the two sides agree in principle – is unsustainable.

The two leaders have spent considerable time on CBMs, and as is often the case in Cyprus, the progress made on some initiatives gets drowned out by the failure to agree on others, quickly becoming emblematic of the historic inability of successive leaders to break the final barrier to a negotiated peace.

When is a crossing a crossing?

So, the sides continue to collaborate on numerous issues – such as crime, foot-and-mouth disease vaccines, and the return and exchange of old bank notes which started last week – but the main issue on the agenda is the agreement last March, at the ‘5+1’ meeting, to open four new crossing points.

The two sides cannot agree on which four crossing points to open, how to count the number of crossing points, and in what sequence they should open. The UN envoy has pointed to the opening of crossings as an important yet minimum signal showing the leaders can find mutually beneficial solutions to problems. And crossings are a problem. The majority of motorised traffic is concentrated at one crossing point, Agios Dhometios, causing huge delays, to the point people – rightly or wrongly – speculate that the inconvenience is intentional to dissuade interaction between the two communities

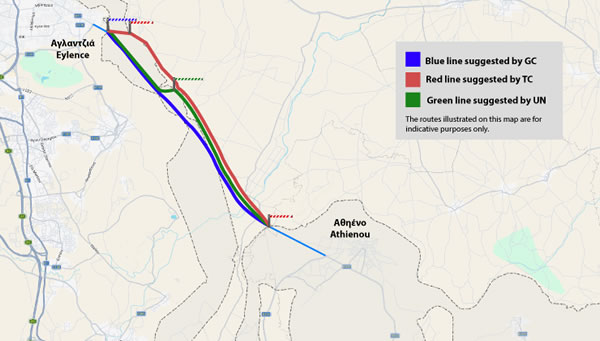

The Turkish Cypriot side considers that agreement has been reached on three crossing points, all to the east of Nicosia: Mia Milia (eastern Nicosia), Louroudjina-Lymbia, and Athienou-Pyroi.

The obstacle remains on the last checkpoint Pyroi-Aglandjia, more specifically on how motorists will get from Athienou-Pyroi to Pyroi-Aglandjia. The Greek Cypriot side wants to utilise the old Nicosia-Larnaca road, which straddles the buffer zone, arguing that the alternative requires a complicated and time-consuming process of expropriating private property in the north to build a new road completing connection of the two crossing points.

The Turkish Cypriot side sees no rationale behind violating the integrity of the buffer zone for so many kilometres, arguing it creates unnecessary security and other complications.

The UNSG offered a compromise proposal last July, which in typical fashion, gives both sides some of what they want. Christodoulides says he’s ready to accept it but so far, the Turkish Cypriot side is not. In fact, the Turkish Cypriots do not even consider there to be an official UN proposal, while the Greek Cypriots point to Holguín herself having tabled the compromise solution in the last two weeks.

Both sides are aware that the issue has started working to undermine confidence as opposed to build it and see the need to turn this dynamic around. But, in terms of their positions, it’s down to the political will of the two leaders to get over this hurdle.

Assuming they do on Tuesday, we still won’t see a package agreement on four crossings because the Greek Cypriot side considers Athienou-Pyroi-Aglandjia to be one crossing point, not two. The fourth crossing point on the list, therefore, is the Turkish army-controlled pocket of Kokkina on the northwest coast of the island. Christodoulides wants to open a route through the military area so local residents can cut the travel time to Nicosia when crossing via the north.

The Turkish Cypriots do not even consider the option on the table, given the “complications” in the area, a likely reference to the fact it is a military site and its symbolic importance to the Turkish Cypriots, given the history of conflict from 1964.

As things stand, the Turkish Cypriot side is ready to open any crossing point on which there is agreement. The Greek Cypriot side wants a package.

If the leaders overcome differences over the route from Athienou to Aglandjia, then technically they could announce the opening of two or three crossing points (depending on your perspective), covering Mia Milia and the Athienou to Aglandjia route.

However, to open Louroudjina-Lymbia, the Greek Cypriot side want to see agreement on Kokkina too.

Solar park gets no sunshine

The EU prepared a feasibility study on bicommunal photovoltaic parks, including two locations with four options on how to set them up and have power sent to the respective power grids.

The Turkish Cypriot side considers discussions on the issue to have been exhausted because the Greek Cypriot side rejected one of the two locations which come as a package.

The Greek Cypriot side argues they have provided options for available locations, but the problem is the question of connecting the parks to the grid in the north, which they consider, symbolically, to undermine as opposed to strengthen the message of reunification.

Given that negotiations reached a dead-end, the sides handed the issue over to Nicosia Mayor Charalambos Prountzos and his Turkish Cypriot counterpart in the north, Mehmet Harmancı, to find ways to implement the project.

'Focus on CBMs a waste of energy'

Speaking to Politis, former Turkish Cypriot negotiator Ozdil Nami argued the notion that CBMs will jumpstart the peace process puts the cart before the horse.

It’s the other way round, he said, adding that a common understanding and vision and good working relationship allow CBMs to start feeding into the process.

“Unless you have a positive atmosphere and progress regarding a settlement, attempts to create meaningful and impactful CBMs always fail,” he said.

Four-point methodology

Then there’s the questions on substance. On the first hurdle, Erhürman wants agreement in principle that a rotating presidency will be part of a solution. The details on when, how and for how long, as well as the question of a ‘positive vote’, can be discussed later.

The main reason behind this request is the Turkish Cypriot belief that Greek Cypriot reluctance to accept genuine political equality was behind the failures in 2004 and 2017.

The Greek Cypriot side considers this a problem, as it unilaterally affirms one aspect important to Turkish Cypriots without reaffirming aspects important to Greek Cypriots.

A possible way around this would be to find a mechanism which confirms all past convergences, including a rotating presidency.

On this second hurdle, the Turkish Cypriot side is looking for acceptance in principle that past convergences – as recorded by the UN – won’t be revisited. Once negotiations resume, if there are different interpretations on the UN-recorded convergences, these can be explored.

Regarding past convergences, the President made a proposal which, according to sources, was misunderstood. He suggested the UN submit a record of convergences and the two sides and guarantor powers (where relevant) have the right to express their views or understanding on those positions, while confirming them as a basis for resuming talks. In other words, as a key to unlock the door to a formal process. And if any side wishes to reopen past convergences, they will be accountable for that.

It’s worth noting the Greek Cypriot side considers the integrated approach of the main issues in the Guterres Framework as part of the body of past convergences.

The third hurdle is accepting in principle to set a reasonable timeframe once the sides agree to start negotiations. For this, the Greek Cypriot side considers that the length of the talks will be determined by the approach to past convergences. If they are accepted, then there will naturally be a very short timeframe.

On the last and most challenging hurdle, to ensure that if the talks fail, and it is not the fault of the Turkish Cypriots, they do not return to the status quo. In 2004, promises were made on ending their isolation which were not kept, they argue. In essence, the Turkish Cypriot side wants assurances before the process begins that they will not be forced to remain in limbo if Greek Cypriots choose not to approve a solution. They do not see this as imposing negative consequences on the Greek Cypriots as a form of punishment, but more as positive consequences for them if they prove their desire for a solution.

This is troublesome for the Greek Cypriot side which views issues such as direct trade, direct flights and direct contact as constituting steps that would lead to the upgrade of the north and seriously damage reunification prospects.

According to former negotiator Nami, “Ms Holguín’s mistake is she’s not focusing discussions on this essential point. She should find a way to get the leaders to open up on this fourth item. If a mutually agreeable solution is found to point number four everything will progress in an accelerated fashion.”

Alternative options

“Insanity is doing the same thing over and over and expecting different results.”

Who actually said that is up for debate, but the point is made. Is it wise to keep trying to achieve a solution after more than half a century using the same methodology?

Professor Neophytos Loizides has put together four proposals on how the negotiations process could be tweaked to improve chances of success, ranging from imposing guaranteed consequences of failure, implementing ‘backstops’ for early gains, holding citizens’ assemblies, and a step-by-step approach to implementation of a solution with a referendum a few years down the line.

The Greek Cypriot side is not keen to change a process that has brought them so far, with great difficulty and over a long stretch of time. However, of the four, it seems the latter option is the one that cannot be ruled out as an idea.

The Turkish Cypriot side finds different ideas useful but considers its four-point methodology as the tool that will ensure the process is not doomed to fail.

As for Nami, he rules out anything that smells of repackaged CBMs, arguing the sides will simply fall into the same trap, get bogged down in details along with the phobia of recognition, losing the essence of the matter, the need for a comprehensive settlement.

He argues against half-measures, noting that even if Turkish Cypriots gained direct flights, it wouldn’t change much. “Direct flights in an unrecognised state will only serve to have more casinos in the north.”

However, setting guaranteed consequences will force the sides to make a decision on what future they want, he argued.

“The time has come… people should be asked to make up their mind.”