Too often, learning remains theoretical, but the most powerful education happens when knowledge meets action. 'Break the Silence', ‘Destinations’, ‘In my room’, and ‘Not as I Thought’ are educational tools designed to empower youth to use critical judgement, protect youth remove italics, encourage victims of to reach out for support educate youth to behave responsibly, showing compassion towards each other and inform parents about the risks faced by their children in the online sphere. What’s interesting is that it’s the result of a project where youth had a leading role.

The Cyprus Police, on Safer Internet Day on 10th February have shared the first two short films on online safety on Facebook and You Tube, created by young people, not through a typical classroom exercise, but through a hands-on learning process that empowered them to become active agents of awareness.

The films were created as part of an Erasmus + Project ‘Film Making for Social Change’ which brought together youth, migrants, and survivors to research, create, and share stories about human trafficking and online exploitation. Through filmmaking, expert training, and cross-border collaboration, participants not only gained knowledge but transformed it into advocacy, equipping communities with tools to protect the vulnerable. The result is four compelling short films that combine real-life insight with creative storytelling, demonstrating how education can inspire tangible social impact.

Led by Katerina Stephanou, CEO and Founder of Step Up Stop Slavery, the initiative spans Malta, Cyprus, and Latvia, combining lived experience with innovative educational approaches to address some of the most pressing challenges facing society and young people today. Throughout the project, the Cyprus Police provided ongoing guidance and institutional support, ensuring that the films accurately reflected official protocols, procedures, and key information.

Behind the scenes of four films impacting many lives

Katerina Stephanou – CEO & Founder, Step Up Stop Slavery

"Our goal was to combine education with lived experience. Learning is most powerful when it is lived, not just taught, and film allows us to convey stories in a way statistics never can."

Step Up Stop Slavery was part of a cross-border Erasmus+ project with Cross Culture International Foundation in Malta, and Shelter Safe House in Latvia. The project included research studies on human trafficking in each country, four-day expert training in Cyprus ‘Access to Experts: Professional Support for Survivors of Trafficking’ designed for multi-disciplinary professionals to strengthen their provision of support to survivors. In addition, it included film-making workshops empowering youth, migrants survivors and civil society to create stories for social change.

The consortium co-wrote and filmed “Not as I Thought” a true story of labour trafficking, depicting the experience of ‘Ahmed, a young man trafficked from Tajikistan to Latvia and forced into an unbearable experience of labour exploitation.

The issue of trafficking for forced labour is increasingly crucial given the huge spike in cases detected globally. According to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) 2024 latest report there is a 25 per cent increase in the number of trafficking victims globally in 2022 compared to 2019 pre-pandemic figures. Between 2019 and 2022, the global number of victims detected for trafficking for forced labour surged by 47 per cent.

“As Step Up Stop Slavery, in collaboration with the Cyprus Police Cyber Crime Unit, we chose to address online exploitation of minors through three educational films, incorporating official protocols and guidance from the Ministry of Education. We had to show there is help available and show the way for victims to reach out for help", Stephanou said.

Katerina Stephanou: I am so proud of our Step- Up Youth team who have created the films - Konstantinos Farmakas, Ariadne Ioannou Panayiotou, Stephanie Liasis, Stephane Noel Tchouanteou, Anna Farmaka, Coulla Karasava and all the children who played, Christos and Eleni Georgiou

Emphasising the seriousness of online exploitation, Stephanou noted that “sharing nude images of children is a criminal offence and can carry a prison sentence of up to ten years. There is no time to delay in reporting, and children can use dedicated hotlines to do so anonymously”. She points out that the patterns of exploitation are not isolated but global, reinforcing the importance of youth participation and education.

“Young people need to be at the forefront of tackling these issues that is why we thought that the artistic expression would be an ideal way to get them engaged”, she stressed, pointing out that around the world, we are beginning to see social media platforms being restricted or banned to protect children, which highlights just how urgent it is to equip youth with the knowledge and tools to act.”

Konstantinos Farmakas: Reality into Film

A film student on the power of the screen, inspiration, responsibility and why empathy must lead prevention

Konstantinos Farmakas, was the director and script writer of the films. The graduate student at the School of Film at Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, reflects on the responsibility of telling difficult stories. His work centres on online exploitation among young people, drawing not from imagination alone, but from lived and documented realities.

He pointed out that from the beginning the team’s choice was that the films were grounded in truth rather than fiction. The films, he explains, depict situations that occur frequently in real life.

Stories rooted in reality

What inspired the storylines of the short films, and how did your own experiences or observations shape the way you portrayed issues of online exploitation among youth?

These are incidents that happen, and they happen often. Many boys and girls are in the same position as our protagonists. The stories are based on real events from actual cases. I would say they are less works of fiction and more dramatised documentaries.

He explains that the creative team held meetings with child psychologists, the Police, the Ministry of Education Cyprus Safe Internet Centre and in order to understand all dimensions and ensure that all official protocols were embedded in the actual films.

Given the short duration of the films, he was conscious that it would be impossible to portray with full accuracy situations that in real life may unfold over days or weeks. With the guidance of specialists, the team selected the elements that were most important to present. The aim was not to replicate every detail, but to capture the emotional and psychological truth of the experience.

Screening for awareness

The aim is that the films are widely screened and reach as wide an audience as possible. Ideally, we would like them to be shown in schools, Farmakas said noting this as an important step, not simply for exposure, but for dialogue.

Now that the Police has shared the films, what key messages or lessons do you hope young people take away from them?

I think people in general ought to have more empathy. At leaste, that was my main takeaway while making these films. These things happen, and often the victims become isolated. As a society, we need to be more sensitive. We need to be comfortable expressing unfortunate realities and helping people come forward with their problems. That is how you fight these injustices.

He argues that predators exist and target vulnerable people, friends and family members, which means vigilance is essential. Accountability, he believes, depends not only on institutions but on collective awareness.

How can your work contribute to real awareness or prevention campaigns?

Every time a bystander dismisses or, worse, humiliates a victim, he empowers predators. This is something that needs to be understood by everyone. I hope enough people see and respond to our films so that we can make more of them, bring light to more stories and inspire the right people to make a difference.

For Farmakas, awareness begins with confronting discomfort rather than avoiding it. Silence and stigma, he suggests, create space for exploitation to continue unchecked.

Film as a tool for social responsibility

The experience of creating socially driven films has shaped his understanding of media’s potential. While cinema has long addressed social issues, he sees new urgency in today’s screen dominated culture.

What have you learned about using media creatively to address serious social issues?

Films have always been used to address social issues. This is simply our attempt to express ourselves on matters we feel strongly about and to raise awareness.

As a youn person, he reflects that in what he describes as the modern screen age, "what is shown often has more impact than what is merely said". People would rather watch than listen or read, and this shift demands adaptation.

How might this experience influence the way you communicate important messages in the future?

In our screen age, what we show has far more impact than what we say. People prefer to watch rather than listen or read, and we must take advantage of that. Screens are everywhere. We need to learn to use them responsibly, and making films for social change is certainly a step in the right direction.

For Farmakas, the camera is not simply a storytelling device. It is a tool of visibility. By transforming real incidents into dramatised narratives, he hopes to challenge indifference, encourage empathy and contribute to a broader culture of accountability.

In a world saturated with images, his message is clear: if screens shape society, then filmmakers carry responsibility. And when used with care, film can become more than art. It can become intervention.

Stephane Noel Tchouanteu – Human Rights Advocate, Founder, Bridge of Hope (TAPSEU PouH) Cyprus

Stephane Noel Tchouanteu is a human rights advocate and community leader originally from Cameroon, now based in Cyprus. His life’s journey has been one of resilience, transformation, and purpose.

He has dedicated his career to advancing social inclusion and justice for vulnerable communities, including migrants and refugees with disabilities.

His work combines community engagement, skills training, and empowerment initiatives, with a particular focus on amplifying the voices of underrepresented individuals.

Through his leadership of TAPSEU PouH, Stephane has established safe spaces for dialogue, capacity-building, and community resilience among displaced populations.

His contribution in the project was crucial as he offered his knowledge gained from supporting vulnerable groups including survivors of trafficking.

"Speaking about difficult topics raises awareness. Many people do not even know trafficking exists in their communities, and through these films, victims’ voices are amplified."

Stephane, brought his lived experience as a refugee and community leader to the project. He co-wrote and acted in the main film ‘Not as I thought’ created by the project consortium about labor trafficking.

He told Politis to the point that through the process he met people and places but also learned a lot himself: “I learned that stories like trafficking and exploitation can come in different forms. And definitely I learned more about the topics”.

"This kind of education breaks stereotypes, builds empathy, and shows that support exists. It is about creating real change through awareness and action", Stephane said.

Ariadne Panayiotou-Ioannou Research Master’s Student of Literature at the University of Amsterdam

“Which voices do we amplify? which voices do we listen to?”

An aspiring writer and literature student shares a glimpse into the importance of dismantling stigma and elevating voices. Ariadne Panayiotou-Ioannou, joined the team as a script-writer with one goal and one wish in mind; to be a part of something that helps voices that are silenced be heard and listened to.

As a student of literature and an aspiring writer, she feels that stories and art are the most powerful tools of resilience. “Art, literature and film are part of resistance, not secondary to it”, she says, hence why she believed so deeply in this project. Ariadne’s research centers around stories and voices that are often silenced or neglected by society, being greatly influenced by her time spent working at the NGO Caritas, listening to stories of asylum seekers and survivors of trafficking.

Upon joining the team, she insisted that the film on labor exploitation be rooted in reality and grounded in fact, so as to be attentive to the red-flag indicators of trafficking, rather than being exaggerated to fit viewership expectations, thus making this film ‘Not as I Thought’ what it is: educational. She admits it was her first time working on a docufiction film, but states that the whole process was life-changing for her as she hopes this is the beginning of a new chapter for Cyprus – a chapter that can inspire attention and listening to stories that we don’t often hear about. Difficult stories. Important stories.

“When shame is louder than support, voices disappear”

The team’s second film, written in the Cypriot dialect, which centers around a teenage girl in Cyprus whose nudes get purposefully and non-consensually leaked by her boyfriend, was a film that Ariadne was also especially passionate about. The film ‘Break the Silence’ offers young people a look into what they can do if their intimate pictures are non-consensually shared online, as well as the legal processes that follow.

Ariadne emphasises that the Cypriot dialect is intentional in ensuring that young people identify with the characters in the film, and to remind people that this is an everyday phenomenon and something that can be resolved.

“Growing up, all I ever heard was ‘don’t send anyone intimate images’ but no one ever told teenagers what to do, if they ever found themselves in a situation where that happened without their consent, or after trusting the wrong person”.

Ariadne states that the team wanted to remind people, especially teenagers, teachers and parents that non-consensual sharing of nudes is a criminal offence and will be taken seriously by the cyber-security police department, with whom they worked very closely to bring this piece to life. The key message, according to Ariadne, however, is the de-stigmatization surrounding the topic and the importance of shifting the blame from the victim to the perpetrator.

“Rather than shaming those whose most intimate images were shared beyond or without their consent, we should start shaming those who commit the crime of ‘revenge-porn’”, she firmly states. She hopes that this film is the first stepping stone towards a future where teenage girls and teenage boys have the courage to step forward and tell their stories without shame, knowing that they will be listened to, helped and respected by their teachers, their parents and the police.

*The screening of Break the Silence will take place on 3 March 2026 at 18:00 at the Amphitheatre Filippos Tsimpoglou, Stelios Ioannou Resource Centre, hosted by the University of Cyprus in collaboration with the UNESCO Chair on Gender Equality and Step Up Stop Slavery.

Break the Silence | Young actors Anna Farmaka and Odysseas Fanis

Inside the Fight Against Online Child Exploitation

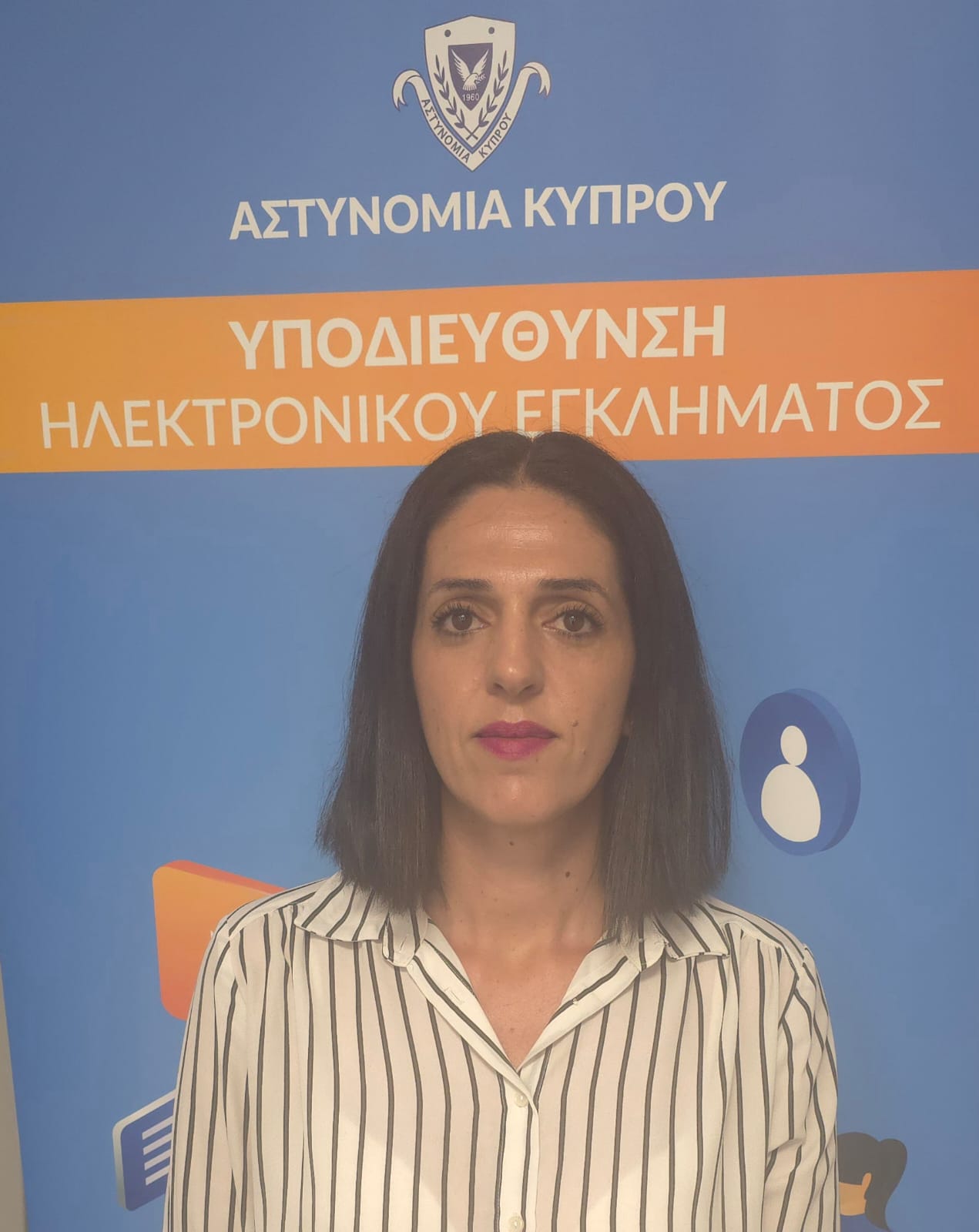

In an age where children grow up connected to screens, the dangers they face are increasingly digital. Maria Pentaliotou of the Cyber Crime Unit, of the Cyprus Police, describes a landscape in which online sexual exploitation of minors remains persistent, complex and often cross border.

Maria Pentaliotou outlines the scale of the threat, the legal framework and why prevention remains Cyprus’ strongest defence

From the outset, she makes clear that children and adolescents are particularly exposed. Many spend long hours online each day and gain access to material, pages and platforms that are not appropriate to their age or level of maturity. Due to their young age, children and teenagers are often characterised by immaturity and impulsiveness, factors that can lead them to underestimate risks or trust the wrong people.

Her Unit has handled cases involving child victims located in Cyprus, as well as cases where offenders obtained child sexual abuse material (CSAM) through the internet. Each case, she explains, has its own distinct facts and circumstances and is treated with strict confidentiality, with the primary concern always being the safety and protection of the child.

The numbers behind the cases

The scale of the issue becomes clearer when examining the annual figures. In 2021, the Unit investigated 214 cases. In 2022, that number rose to 237. In 2023, 203 cases were recorded, followed by 208 in 2024 and 201 in 2025.

The numbers fluctuate slightly from year to year, but remain consistently high. They form a steady statistical framework that reflects the ongoing nature of online child exploitation and the sustained workload faced by specialised investigators.

For every unlawful act and inappropriate behaviour, there is a separate article of the law providing for different penalties depending on the elements of the offence. Pentaliotou notes that in recent years the courts have begun imposing stricter sentences for crimes involving the sexual abuse of children. For certain offences under Law 91(I)/2014 of the Republic of Cyprus, penalties may extend up to life imprisonment.

Understanding vulnerability

What would you say to young people about online sexual exploitation and abuse?

Children and young people need to understand that not everyone online is who they claim to be. Fake accounts and false identities are common tools used by offenders. If something happens online that makes a child feel uncomfortable, frightened or confused, they must speak to a trusted adult without shame or fear. The Cyber Crime Unit has trained officers who can listen, provide safety and refer children to specialised professionals where necessary.

Are there specific age groups that are more vulnerable?

In general, children are more vulnerable than adults because of their young age. Vulnerability is closely linked to developmental immaturity rather than to a specific age bracket.

What happens when a case is reported

When a suspected or confirmed case arises within a school or community, clear procedures are activated. There is a protocol issued by the Ministry of Education regarding the handling of suspicions or findings of child sexual abuse. The Police and the competent department are informed immediately in every case.

The relevant legislation includes an article that obliges any person, and particularly professionals such as teachers and police officers, to report such incidents to the competent authorities.

What are the first steps once a possible case is identified in a school environment or online?

Immediate notification of the Police is essential. Dedicated support and reporting lines are in place, and parallel psychosocial support procedures are activated. Once a report is made within a school, the child protection network is mobilised to ensure coordinated action and the safeguarding of the child.

Police departments dealing with these offences cooperate closely with the Children’s House, operated by Hope for Children, as well as with Social Welfare Services and other state bodies and non-governmental organisations. This collaboration ensures that the child receives comprehensive care while the investigation proceeds.

We say “sweet dreams” and close the door. But the real question is: who’s on the other side of the screen? Make sure the window to the internet doesn’t become a nightmare.

Prevention as protection

Beyond investigation and prosecution, prevention remains central to the Unit’s strategy. Officers provide lectures and presentations to children, parents’ associations and other organised groups connected with young people. They participate in conferences on online safety and attend events and meetings focused on digital protection.

Which prevention activities have had the greatest impact, and why is investment in them so important?

Lectures, awareness campaigns and community engagement initiatives have real impact because they focus on prevention through information. Investing in prevention is essential, as it protects children from incidents that may have serious and long-lasting negative consequences.

A cross border battle

Identifying offenders is often extremely difficult, particularly because cyber crimes frequently cross-national borders. Pentaliotou explains that these investigations require modern technology, continuous training and collective effort.

Through ongoing staff education, advanced equipment and cooperation with international agencies such as Europol, Interpol and the FBI, the Unit has achieved a very high level of effectiveness in identifying perpetrators involved in online child sexual abuse. Members participate in international operations, exchange knowledge and expertise, and take part in joint investigations.

Cyber-crime is inherently transnational. Protecting children in the digital age, she makes clear, demands constant vigilance, coordinated institutions and an informed society willing to act early rather than too late.